How pieces of ancient pottery from a village in northeast Thailand challenged prevailing ideas of the prehistory of Southeast Asia, how it fell prey to international smuggling, and what’s being done to return the smuggled items to Thailand

Fifty years ago in August, in the village of Ban Chiang near Udon Thani, a visiting American student named Stephen Young tripped over an exposed tree root and fell atop the rim of a clay pot partly buried in the village path. His tumble set into motion two joint Thai-American archaeological expeditions to Ban Chiang in the 1970s that exposed the extent of prehistoric burial sites beneath the village, sites filled with thousands of pieces of pottery and metalwork buried as grave goods by Neolithic and Bronze Age peoples at different times between 4200 and 1800 years ago. The Ban Chiang finds revealed unexpected technological and artistic development among the peoples of the region and challenged prevailing ideas about the prehistory of Southeast Asia.

Dr. Joyce White, Scientific Director of the Ban Chiang Project at the University of Pennsylvania Museum

American archaeologist Dr. Joyce White is the Director of the Ban Chiang project at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, USA, where she has studied the finds from Ban Chiang since 1976. She is an expert witness for the US Department of Justice in an ongoing antiquities trafficking case that in 2014 resulted in the return of many smuggled Ban Chiang items to Thailand.

Dr. White recently spoke to The Isaan Record about the legacy of the discoveries at Ban Chiang, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage site and a renowned archaeological museum.

IR: For archaeologists, what have been the most important discoveries at Ban Chiang over the last 50 years?

Ban Chiang’s contribution to understanding the past is ever-evolving — what one archaeologist thinks is important another disputes and thinks something else is important. Moreover, some aspects of the ancient society need a great deal of more investigation and publication.

But there are two portions of the data that have now been thoroughly studied: the human skeletons, which are fully published, and the metallurgy, which is close to being published. Results from intensive study of these two datasets are important for debunking long-held stereotypes about the human past that derived from long-term archaeological research in the Near East, Europe, and Central America.

IR: What do the skeletal remains and metallurgical finds show?

The Ban Chiang skeletal evidence revealed that metal age agrarian societies in that part of Thailand were notably healthy and peaceful – [there is] no evidence for interpersonal violence consistent with regular warfare. The metallurgy was used for symbolic and utilitarian purposes. Only late in the Iron Age in the Upper Mun Valley (at Noen U-Loke) is there evidence that some amount of warring was occurring.

Bronze Age skeleton with jars as burial goods at Ban Chiang. Photo credit: Ban Chiang Project / Iseaarchaeology.org

Significant ill-health is found in some prehistoric skeletal populations along the coast (at Khok Phanom Di in Chonburi province). But in Isaan, on the whole, people got along and ate a good diet. These results contrast with evidence from some other parts of the world listed above where population health declined with the adoption of agricultural economies, and metallurgy stimulated warring interactions.

IR: How have the discoveries at Ban Chiang challenged prevailing ideas of the prehistory of Southeast Asia?

These “discoveries” are still being digested by the field. It is so easy to want to sensationalize the past, and disease and trauma evoke emotions and attention that health and peace do not. But in my view, whenever archaeologists discover societies that vary from some expected “norm”, these are the societies that make fundamental contributions to understanding human diversity that “typical” societies do not.

The next step is to figure out why and how the prehistoric societies of Isaan established and maintained these peaceful healthy lifeways, and technically sophisticated but modestly-scaled metallurgy. I give a stab at that in the concluding chapter of the forthcoming Ban Chiang metals monograph, essentially relating the evidence to resource distributions and a dynamic networked regional economic system that had great time depth.

IR: What was daily life like for the Bronze Age people who lived at Ban Chiang?

We still need to undertake various studies to really understand the Bronze Age lives of Ban Chiang peoples. However, from what we know so far, I believe that much of their time was spent acquiring food from many different activities.

Plants were cultivated, including rice, but probably many other species as well. Animals were both bred and hunted. Many wild resources were collected, such as wild plants like yams, mollusks, frogs, and fish, with the activities varying depending on the seasons and the natural patterns of these resources, similar to subsistence activities in traditional Isaan villages today or the recent past.

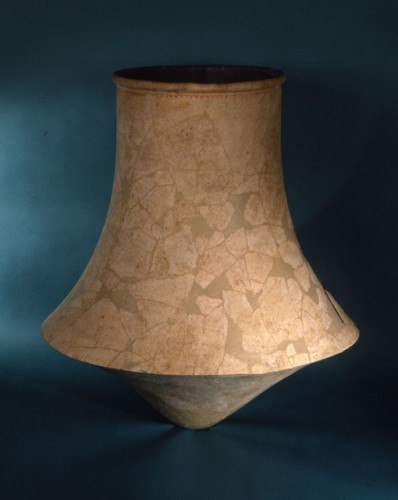

A tall white hyperbolic carinated vessel from the Middle Period at Ban Chiang, circa 800~400 B.C. Photo credit: Ban Chiang Project / Iseaarchaeology.org

The dry season was a time for craft activities, and clearly a lot of effort was expended in making pottery beyond what was needed just for cooking and storage. Pottery (and possibly other crafts like basketry) clearly was one means of aesthetic expression and a means of social networking. And social networking was a major focus, both within villages and village to village. Although some lands were cultivated, vast tracts were likely pristine forests, as [the] population density would have been much lower than today.

IR: Which of the items found at Ban Chiang is your favorite?

Excavated items that are “favorites” can appeal on a variety of levels. From an aesthetic point of view, I love the tall white carinated pots from the Middle Period. I have nicknamed them “Three Mile Island Pots,” an allusion that many may find obscure, but with audiences of a certain age and geography, the nickname can get a reliable and solid laugh. Essentially these pots have the shape of nuclear cooling towers, such as those at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, where a nuclear accident occurred as we were reconstructing these pots at the Penn [University of Pennsylvania] Museum in the 1970s.

These vessels, which I have more formally dubbed “tall white hyperbolic carinated vessels’, are astonishing for their technical virtuosity and contemporary flare. How ancient potters made these large concave-sided, thin-walled vessels (often only a couple of millimeters thick) with creamy-white exteriors using paddle and anvil shaping and open-air firing remains to be fully understood.

Also intriguing is that these pottery vessels were usually deliberately broken over the bodies in the grave ritual. Without painstaking reconstruction, we might never have known about this type of pottery!

In 1971 Ban Chiang attracted the attention of antiquities dealers when an erroneous dating test on one of the famous pots suggested it might be much older than it was. This caused a spike in demand for Ban Chiang items and extensive looting at the Ban Chiang site, and thousands of pieces of Ban Chiang pottery began to be smuggled out of Thailand. Many found their way into museum and art gallery collections overseas, and many fake Ban Chiang items were also fabricated and sold.

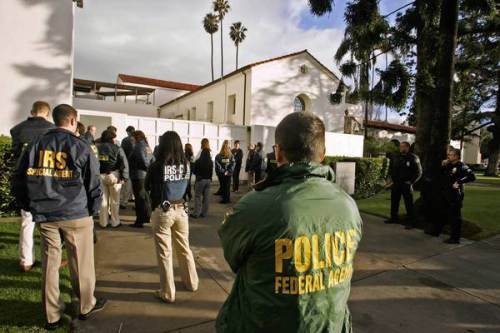

In 1972, Thailand’s King Bhumibol visited Ban Chiang and urged to better protect Thailand’s cultural heritage. After his visit Thailand banned the export of all items from Ban Chiang without approval, expanding on a 1961 law that controlled the export of antiquities. Those Thai laws now influence an ongoing antiquities trafficking case in the United States, which hit headlines in 2008 when federal agents raided several museums and businesses. In 2014, many pieces of Ban Chiang pottery were among the first items returned to Thailand under the investigation.

Trainee Lionel Chiong from the Philippines, now a Southeast Asian archaeologist, at work in Ban Chiang in 1975. Photo credit: Chester Gorman / Ban Chiang Project / Iseaarchaeology.org

IR: What have been your key experiences as an expert witness in the US investigation into trafficked Ban Chiang antiquities?

Gosh there have been so many … One was as the [attending] expert for delivering a search warrant at one of the target “museums” in the Midwest. About 100 law enforcement officers (LEOs) and I descended upon this private museum one early, extremely cold morning. Once the place had been “secured” by the bullet-proof jacketed LEOs, I was brought in … to authenticate and classify hundreds and hundreds of objects in a matter of hours at this extremely posh establishment. This was quite a test of my knowledge, [there was] no time to ponder any individual object.

US Federal Law Enforcement Officers raid the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California in January 2008. Photo credit: LA Times/ Ban Chiang Project / Iseaarchaeology.org

Over months, I authenticated more than 10,000 prehistoric Thai artifacts that had been smuggled from Thailand since about 2003. This type of task was and is profoundly disturbing for an archaeologist. It was clear that hundreds of sites had been destroyed, vast amounts of Thai archaeological resources had been severely damaged. I felt sick. I felt and still feel sad for Thailand and sad for archaeology.

IR: Can any lessons be drawn from Ban Chiang about the protection of archaeological and cultural heritage?

There are so many “if-only’s” — if only there was proper funding for archaeology, in all its aspects, from the education of nascent archaeologists to scientific analysis by experts to proper publication at international standards. If only all the resources that had gone into destroying those sites, smuggling the artifacts out of the country, selling them to collectors, and displaying the objects in their custom cases had instead gone into archaeological investigation, the archaeological resources could have been used to develop both knowledge about Thailand’s deep past and the use of those resources [could contribute to] rural development by developing tourist destinations with meaty presentations.

To develop these cultural resources in sustainable ways takes money, it takes expertise acquired from years of scientific education and experience, and expertise in presenting this kind of material in an engaging way to a general and international public. I do think the museum at Ban Chiang is a fantastic case study of how to develop an archaeological resource with excellence. I want everyone in Thailand to go visit that museum and ponder the possibilities of how they can help make that the norm, not just the exception.

IR: To what extent does looting still threaten scientific knowledge and heritage in Southeast Asia?

Looting remains a devastating force for Southeast Asian heritage and for scientific knowledge of the region’s past. When one looting and smuggling ring is exposed and possibly dampened, another one crops up, perhaps shifting its focus to ancient Cambodian or Vietnamese cultures and a different avenue of distribution and marketing.

Public education to NOT purchase antiquities and thereby dampen the market needs to be ramped up, but law enforcement also needs to be ramped up, with meaningful international cooperation to stem the international market — all of which takes resources and the political will to face the sometimes powerful individuals who collect antiquities.

IR: Does land development also present a threat?

It is true that the forces of development are also having a devastating impact on heritage resources. Whole sites and thousands of years of evidence can be wiped away by a couple of days of bulldozing at a location for an apartment building that will probably only be standing a couple of decades. Rivers that are dammed drown hundreds of sites that could have told important stories of the region’s past.

My number-one recommendation for all development projects is that an archaeological assessment take place prior to any construction, and if sites are found they should be excavated and studied. The costs for this should be built into the development budgets and project timelines.

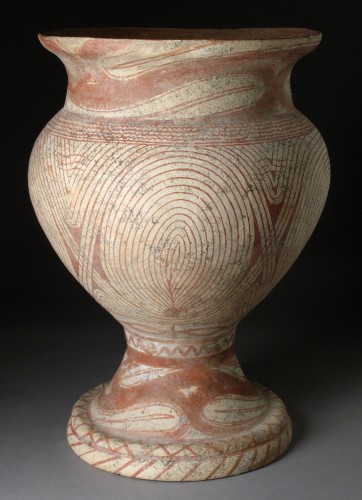

Late Ban Chiang pottery, circa 300 BC to AD 200, at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art (LACMA). Photo credit: LACMA / public domain

IR: How can archaeological scholarship benefit modern communities, at Ban Chiang and at other sites?

Ban Chiang is a heritage resource for Thailand, for Southeast Asia, for the world. Like any resource — human, natural, or financial — it can be developed in ways so that it will continue to give to society, or it cannot be developed [and will] be allowed to wane. It is up to the society to make the choice.

Ongoing world-class scholarship is critical to sustainable development of heritage resources, especially archaeological resources. Development of heritage resources depends on engaging public audiences, both national and international.

Ban Chiang could serve as a best-practices model for how to both study and communicate effectively about ancient societies for the benefit of all. This could include both behind-the-scenes management of scientifically excavated collections, which can be studied in perpetuity by visiting scholars (Thai and non-Thai), as well as public museum displays of “what’s new” and “ongoing research” that keep the public engaged in the processes of discovery.

IR: What are your hopes for the next 50 years at Ban Chiang?

My dream is that Ban Chiang becomes a regional center for the study of ancient life in the middle Mekong Region. Public outreach could be greatly enhanced in several ways. The quickest way for now is to develop marketing approaches that bring audiences to the Sakon Nakhon Basin for several experiences over a few days. Udon Thani should work with neighboring provinces to develop “packages” of experiences to market to the tourism sector. Lao citizens and residents and visitors to Vientiane are a particularly suitable audience that has not been developed.

With Ban Chiang and Udon Thani taking the lead in developing a model for an archaeology-outreach partnership, other parts of Thailand and Southeast Asia can use the model to implement their own heritage development plans. All for the economic betterment of local communities, for archaeological knowledge of the human story, and global knowledge of this part of Asia’s deep history.

The Fine Arts Department and Udon Thani province are sponsoring an international conference about Ban Chiang from 26-28 May 2016, in recognition of the 50th anniversary of Stephen Young’s discovery of Ban Chiang in 1966, featuring presentations on archaeological scholarship and outreach and a visit to the Ban Chiang Museum and dig site.

The Ban Chiang Museum and dig site are in Ban Chiang village in Nong Han district of Udon Thani province, about 50 kilometres east of the city of Udon Thani. The museum is open from Tuesday to Sunday each week and on holidays, from 9am to 4pm. Telephone: +66 4232 5406/7.