By Peera Songkünnatham

[Contains spoilers.]

“You’re just like me: old, fat, and homeless,” says Thana, brooding over his mid-life crisis–with a sweet marriage turned sour, a stellar career fading into irrelevancy–to Popeye, his elephant companion, which he met earlier in the streets of Bangkok and recognized it as the same elephant he was once friends with as a child in the rural Northeast.

A feature debut by Kirsten Tan, a Singaporean filmmaker based in Brooklyn, New York, Pop Aye is an enjoyable journey of a middle-aged man and his long-lost elephant. The film strikes a balance between drama and comedy, and perhaps only stumbles in its sex scenes that come off more awkward than effective. While its tagline claims that Pop Aye is a story about a man bringing an elephant home, the reverse is more true–it is a story about an elephant bringing a man home. I would even go further and say that this story isn’t about the elephant at all.

Singaporean Kirsten Tan’s feature debut, Pop Aye has toured international film festivals and won awards from Sundance and Rotterdam.

Thana, the film’s protagonist, is a Bangkok architect whose only surviving connection to his hometown in Loei is an uncle whose phone number he’s lost. The actor Thanet Warakulnukroh’s near inability to speak Lao is surprisingly fitting. The only Lao he ever speaks in the film is a mutter bo pen nyang (I’m okay) in response to his uncle’s question bo pen nyang ee-lee ti (are you really okay?). Other than that line, he talks to Lao-speaking characters with standard Thai. As such, he delivers the jarring effect of homecoming to a place he no longer recognizes.

After thirty years away, Thana finally comes back to his hometown and faces a rude revelation: the “home” in his memory is just that, a memory. Isaan today is no longer the Isaan of his childhood where he and other village kids would watch Popeye on a television set in his uncle’s dirt frontyard. Toasted rice snacks (known in Isaan as khao bong – puffed rice or khanom hu chang – elephant ear–a felicitous name!) that he hasn’t had in so long now come prepackaged in plastic and sold in Tesco Lotus minimarts.

As it turns out, Thana takes part in that change as well. His nostalgia is akin to that of an imperial agent: he yearns for something he himself has destroyed.

Once Thana arrives in his hometown Loei, the audience learns through his uncle’s words that it was Thana who sold the young Popeye for the money he needed to move away and make it as a Bangkok architect who goes on to design luxury skyscrapers.

“Now you miss home?” quips Thana’s uncle, played by renowned Isaan performer Noppadol Duangporn of the band Phetchpintong. While the opposition between Isaan and Bangkok might seem too black-and-white, it does work in this case: for natives who abandon their small town for the metropolis, there may not be any turning back.

During the journey from Bangkok to Loei, most memorable are the side characters Thana encounters–an aging kathoey past her prime of “a few good years” in Bangkok, a scraggly-looking fortune teller living off the grid, his long lost lover who has moved on, and an old man with an 8-year-old son. Penpak Sirikul, who plays Bo, Thana’s hi-so wife, holds the emotional arc of the story together with her subtle acting that shows a quiet progression from being standoffish to tender.

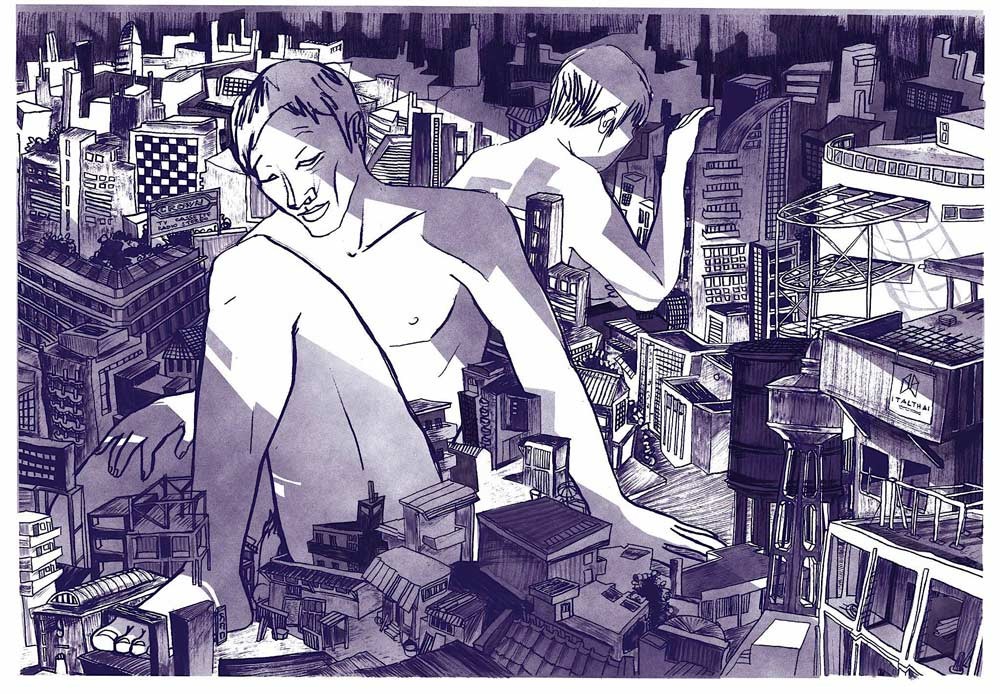

The moods of Bangkok’s skyscrapers, the Central Plains’ industrial highways, and the roads, hills and paddies of the Phetchabun mountain range are ably captured in Pop Aye’s visual frame. Its road-movie quality is enhanced by an eclectic soundtrack of full-length songs and a delicate production design that are in tune with the Northeast’s landscapes and different dialects of Lao.

Plai Bong and Nong Oratai, Surin elephants starring in Pop Aye as adult and young versions of the elephant Popeye, respectively. They walk the red carpet in the event before the premiere screening of Pop Aye prior to its commercial release in Thailand at SF City Cinema, Robinson Lifestyle Center, Surin City.

This Monday, Pop Aye premiered in the Northeast prior to its nationwide release in Thailand. Interestingly, it was organized in Surin, Thailand’s “Elephant Town” which borders Cambodia–a rare event as most “red carpet” events happen far away in Bangkok. Leading up to the screening was a motley of localism and nationalism–from kantrum dance and music to a song praising the arts (ศิลปาธร) of the “Siamese.” The event was headlined by the Surin’s Governor who, in a very Thai bureaucratic style, gave out dozens of certificates, posing for photographs alongside the movie’s starring elephant Plai Bong.

Of note was the presentation by the conservation NGO Elesystem (in Thai Thammachang, a portmanteau of “elephant” or chang and “ecosystem” or thammachat). Recently founded and run by people in Surin, Elesystem fosters the method of “returning elephants to the wild” and conserving and rebuilding elephants’ habitats. They describe elephants as a keystone species which shapes the forest ecosystem and holds it together. As a symbol, the elephant has been used for the Siamese and Vientianese flags during their absolute monarchies, to the current logos of Thai conservation organizations.

Near the film’s end, Thana speaks of giving Popeye to an elephant reserve. The fate of Popeye is left ambiguous; even Popeye’s existence can be called into question by the end of the movie. In a way, Popeye can be read as one large metaphor in the story.

Of the parallels Thana draws between himself and Popeye–“fat, old, and homeless”–I find the last one to be most intriguing. What is a domesticated elephant’s home? Definitely not the urban jungle, where Popeye’s ears are rubbed raw by the mahout’s steering rope, where his feet bleed from treading the burning asphalt of the streets. And yet, his home is not the human town of his origin, either, as it has now urbanized into apartment complexes.

An elephant reserve, it seems, is more a refuge than a true home. According to the video shown by Elesystem at the premiere, elephants raised among humans don’t think of themselves as elephants but as humans. To return such elephants to the wild requires extensive processes of reintroduction to “reawaken their instinct,” and not every domesticated elephant is able to be successfully “returned.” While Thana is able to return to Loei and make peace with life at “home” in Bangkok, we don’t know if Popeye ever finds a home, or whether he has a home at all.

Incidentally, the elephant also acts as an effective PR boost, carrying a host of associations with localism (Surin-ness), ethnic identity (the Kuy mahout tradition), nationalism (Thai-ness), and biodiversity conservation ideology (keystone species).

The figure of the elephant has proved so charismatic that now it also carries a man facing mid-life crisis on his journey home. Pop Aye is about a middle-aged man facing a midlife crisis. It is a road movie about coming to terms with living and dying. It isn’t really about elephants, yet everywhere you look around here, there’s an elephant.