By Peera Songkünnatham

It’s 2018, and the age-old trope in Thai media of Isaan women as domestic servants hasn’t died out just yet. This time, the trope gets parodied by a drag queen portraying an upper-class woman.

Drag queen Natalia Pliacam gives a spot-on performance as 80-year-old Thai socialite Sumanee Gunakasem, also known as “Thailand’s Barbie doll.” She sits next to Dearis Doll, who impersonates Jintara Poonlarp, a molam singer from Roi Et who is still at the top of her game after thirty years in the show business.

Motioning to a bottle of cosmetics right in front of her, Natalia Pliacam turns to Dearis Doll and asks:

“Help me pick this up, please . . . Thank you very much. [points to the helper] Actually she’s my house servant.” [watch the full segment on LINE TV here]

This interaction comes from a celebrity impersonation challenge in reality TV show Drag Race Thailand, where contestants are encouraged to play up their character and be funny. The episode aired in March this year.

What is so funny to the judges about this moment? Does humor lie in recognizing the ridiculousness of rich Bangkokians’ typecasting of Isaan people? Or does it lie in the tradition of Isaan people being the butt of the joke?

The latter, I fear, probably plays a part.

Crossing ethnic/racial lines in drag

Contemporary drag performance is all about being transgressive; it is not supposed to be agreeable, much less “politically correct.” One of the things drag queens on RuPaul’s Drag Race often say to each other is “Aren’t we all just men in wigs?”

Yet, drag queens don’t always get away with racist jokes. The original American show RuPaul’s Drag Race, on which Drag Race Thailand is based, has had various responses to racist jokes itself.

Way back in Season 3 of RuPaul’s Drag Race which aired in 2011, Manila Luzon, a contestant of Filipino descent, portrayed a Chinese television reporter with a stereotypical eagerness to find an American wife for her “blah-ther” (brother) so he can immigrate to the United States.

While a fellow contestant criticized her for mocking an ethnic group she is not part of, host RuPaul Charles gave Manila Luzon a win for the performance:

“Manila Luzon, this week you broke all the rules, you crossed the line of good taste and you perpetuated stereotypes. [pause] Condragulations you’re the winner of this challenge.”

However, in the following season, an opposite response occurred. In a challenge where contestants deliver political speeches to be the first drag president of the United States, there was another racist joke.

Contestant Phi Phi O’Hara plays a stereotypical racist lady politician from the South and gestures to her two black competitors, calling them her domestic servants.

“I think it’s so great that the help can sit there and compete alongside me. So I’d definitely like to say, my help: DiDa Ritz!”

To this, DiDa Ritz, one of the black competitors, reacted with shock, while the other had a stern face.

Later, one of the permanent judges, Michelle Visage, criticized her joke: “in order to land an off-color joke, it has to be funny. And that joke came across as offensive.”

Isaan women as “the help” of wealthy Thais

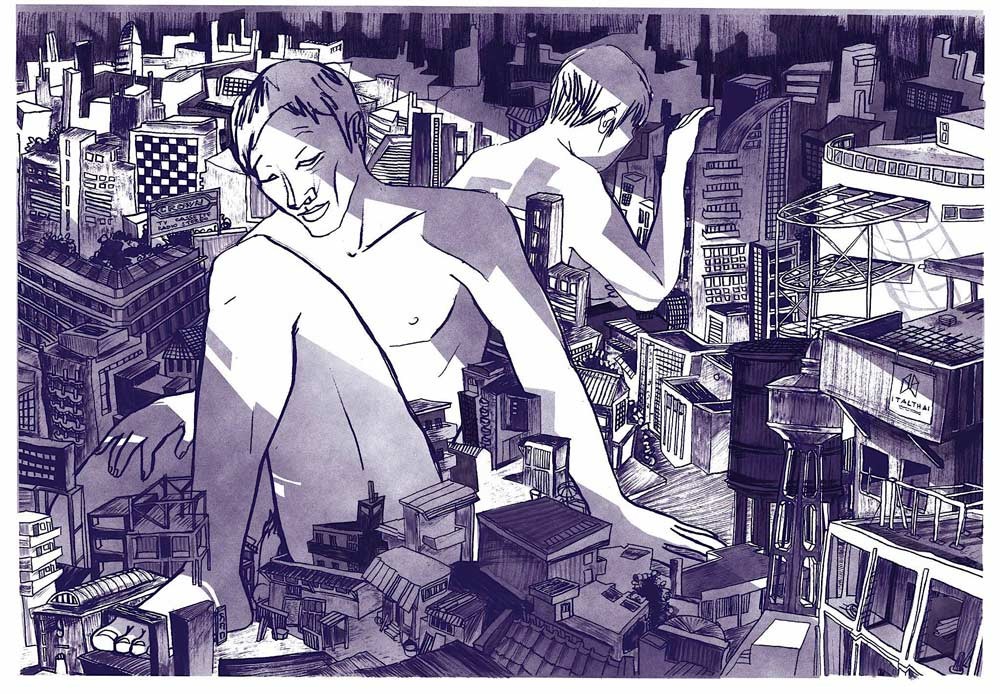

Thailand, too, has its equivalent of “the help,” in the girls and women from the rural Northeast. Known as jaew, the figure of the Isaan housemaid has had many incarnations in TV shows and movies: from mere extras to full-blown protagonists. Invariably, these jaew characters provide comic relief and are portrayed as more innocent — which could either mean “adorably noble” or “laughably ignorant” — than wealthy urban people.

In his 2016 book Sociology of Isaan, Supee Samorna identifies the media trope of “jaew” as an instrument of false consciousness that, reproduced over and over with an exclusion of diverse representations of Isan people, insidiously makes Isan people believe in the false idea that our given role in society, our fate, is to be a lifelong servant: khi kha.

Even the most positive portrayal one could find of the jaew trope still doesn’t lead to the Isaan servant transcending her subordinate social position.

Based on a popular comic book series, comedy musical movie Noo Hin (2006, directed by Komgrit Triwimol) tells the story of Noo Hin as she leaves her home village in Ubon Ratchathani to find work in Bangkok, fantasizing about glamorous work in a modern factory. Once she lands a job as a live-in maid with a wealthy family, Noo Hin eases into her “house manager” role and gets along with the two khun nu sisters obsessed with the latest beauty trends.

Throughout the rest of the story, Noo Hin does many good deeds: enrolling her two mistresses in a modeling competition, then catching a rich man sneaking into the dressing room snapping photos of her masters, and then rescuing enslaved Isaan sweatshop workers. Finally, her two masters win the modeling contest, and Noo Hin proves herself to be a moral example as well as fashion inspiration for the French designer headlining the contest.

Upward social mobility for Noo Hin may mean getting to fly to the world’s fashion capital, but it does not mean terminating her servant position. Class hierarchy remains undisturbed. The jaew’s role remains that of bringing levity and happiness to wealthier people around her.

The jaew’s narrative arc, even at its most glorified, does not lead to becoming an independent entrepreneur the way it has happened in reality many a time, when former maids are spotted by their former masters right around the street’s corner selling som tam and kai yang.

A popular chatting sticker set featuring a Lao-speaking Noo Hin, created in 2015 by Withita Animation Co. Ltd. Source: Prachachat

Making fun of Isaan people

Beyond the trope of the Isaan housemaid, Isaan people with a particular set of facial characteristics and hairstyles have often been depicted as comedic, even when they aren’t comedians. Jintara Poonlarp, with her signature bob and her flat nose, somehow fits in this comedic mold.

The problem with making fun of Isaan people, then, is that it is so normalized it’s not even seen as a sensitive issue.

Like the “my help” comment of Phi Phi O’Hara playing a stereotypical racist Southern politician on RuPaul’s Drag Race, Natalia Pliacam’s “my help” comment on Drag Race Thailand is a spot-on parody of upper-class demeanor and patronizing attitude.

In a 2017 interview, Sumanee Gunakasem expressed her role as patron toward her servants. She said that since being diagnosed with ovary cancer, she has been preparing to get her “retainers” (boriwan) taken care of even after her death, “lifelong sustenance” like masters in old times.

But unlike the American case, Natalia Pliacam’s joke isn’t just accurate; it also works. The judges laughed out loud. I myself laughed, but I also gasped in shock.

Natalia’s racist joke (there I said it) gets a pass not just because it lands, but also because the all-too-familiar trope of Isaan women as servants is not seen as a “sensitive” topic in the first place.

As for Dearis Doll, she delivered some funny lines as Jintara Poonlarp. Unfortunately, the drag performer couldn’t speak Lao, and so half butchered her “Isaan accent.” But nobody in the room seemed to take issue with that. Dearis Doll’s performance was still received as “funny” and passed as a loving homage.

My aim here is not to criticize Dearis Doll or Natalia Pliacam. All my scrutiny is meant to point out what this interaction and reaction represents in the larger context of the show, which I treat as a microcosm of Bangkok-centric Thai media at large.

Included but not called by name, parodied but not proudly presented

Drag Race Thailand participates in the erasure of Lao ethnicity in Isaan under the national label. In the same breath, it showcases Chinese heritage in its premiere episode which coincides with Chinese New Year.

One of the guest judges is Madiew, a 19-year-old fashion designer from Khon Kaen whose claim to fame was her making and modeling haute couture dresses out of everyday village materials, including firewood, mosquito nets, and zinc roofs.

The show’s host, though, did not mention Madiew’s northeastern origins, but only introduced her as “the youngest sibling in the Thai fashion circle who’s gone international.” In effect, Madiew “blends in” with her fashionable family dominated by Chinese-Thais. Her difference in origin needs not be mentioned.

True to her style, fashion designer Madiew from Isaan interpreted the “Chinese New Year” theme and came out with a dress, earrings, and headpiece made of firecrackers in the premiere episode of Drag Race Thailand.

All these things together illustrate the state of Isaan in Thai media: included but not called by name, parodied but not proudly presented.

This shouldn’t be big news to anyone. Drag Race Thailand itself has had to reckon with overt racial prejudice in its Thai fanbase. Jaja, one of the show’s eight contestants, hails from the Philippines and doesn’t speak Thai. A Facebook fan page posted a racist tirade against Jaja and possible Filipino contestants in the future.

Among the epithets, Jaja’s face was compared to “someone who drank rice whisky and didn’t sleep.” Rice whisky, or lao khao, is incidentally the alcohol associated with low-income Isaan villagers. Somehow, the Northeast is linked to the unwanted foreigner.

As a result, many contestants came together to show love and appreciation for Jaja, led by the show’s co-host.

Which begs the question, what about Isaan? When will Thai TV producers reckon with their own treatment of the Northeast?