SPECIAL SERIES: SWEETNESS & POWER

Greenpeace recently reported that, “Air pollution in Thailand is responsible for cutting short 50,000 lives every year.” Air-quality data is critical to tackle Thailand’s annual air pollution crisis. But in Isaan, the country’s largest region, the problem remains invisible as most provinces have no pollution monitoring systems in place.

PART XIII: With air pollution invisible in Isaan, millions will be breathing unhealthy air

Apichat Suvannasing finally lost the painful chronic cough that just wouldn’t go away for seven months. But the 30-year-0ld dentist at a local hospital in Nong Bua Lamphu’s Na Wang district is worried that come next sugarcane harvest season, the condition will return.

“Seven months of coughing, sometimes so hard it hurt my ribs, was a very painful time,” he says, “and I don’t even have any allergies.”

Apichat had just returned to Nong Bua Lamphu from several months of training up North last year when he noticed the bad air. He started to have trouble breathing and fell sick in October, around the same time when sugarcane farmers begin to set their fields on fire before the harvest.

Hospital data records relayed to The Isaan Record from hospital officials in Nong Bua Lamphu province show a spike in patients with asthma and respiratory illnesses during the same period from October 2018 to March this year.

The government recognizes air pollution as a serious threat to public health, not only since Bangkok’s air became one of the world’s foulest earlier this year. But while the capital, the Central region and the North have constant air quality monitoring, most provinces in the Northeast are located in an air pollution “blindspot.”

With seasonal smog set to become worse in the region that grows most of the country’s sugarcane, local pollution control agencies in the Northeast are ill-prepared to address the next smog crisis.

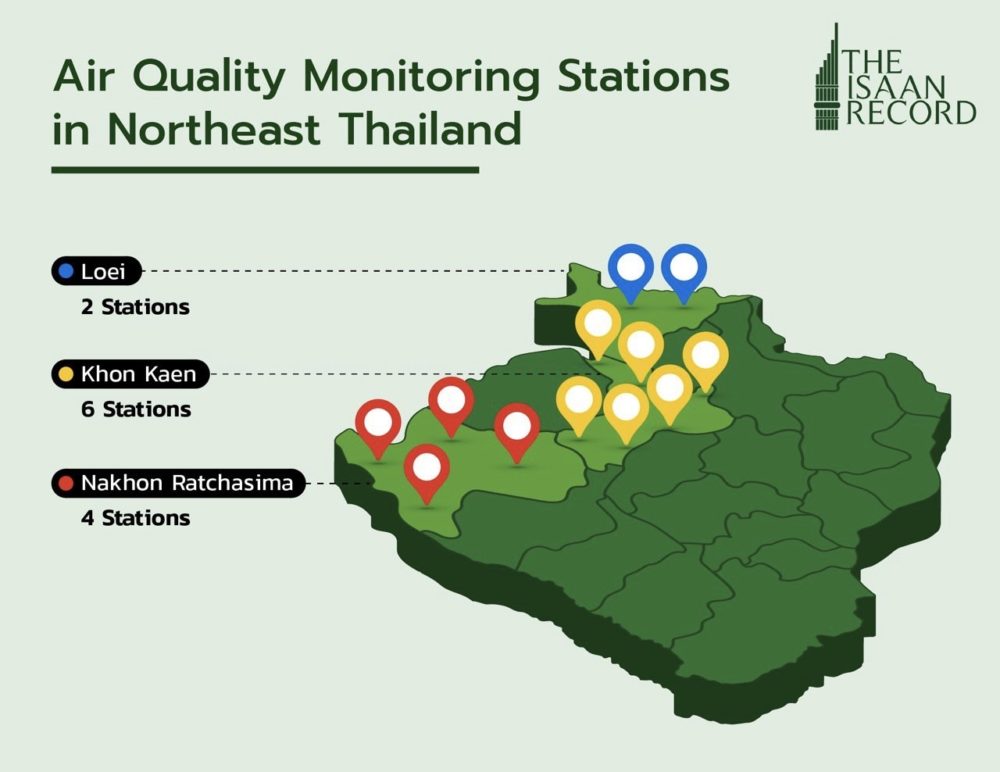

There are 12 air quality monitoring stations in three provinces in the Northeast but not all of them could pick up the most dangerous type of pollutants. The Pollution Control Department website only lists three stations in the Northeast that fully measures pollutants. The remaining 17 provinces have no air-quality control system in place.

Isaan, invisible air pollution hotspot

Thailand’s annual haze crisis was particularly severe early this year when the air in the northern city of Chiang Mai briefly became the most polluted on the planet and Bangkok cracked the top ten of cities worldwide for the worst air quality.

Khon Kaen province was hit by toxic haze for several weeks in February and March as the local pollution control monitor recorded “very unhealthy” levels of air pollution.

It is one of only three provinces in Isaan where authorities have access to real-time air-quality data. In the other 17 provinces in the region, the only place where air pollution is recorded is in people’s lungs.

Interviews that The Isaan Record conducted with pollution control officials, experts, and locals in the region, as well as satellite images and data from handheld air quality monitors suggest that air pollution has also reached critical levels in other places in Isaan. It has been especially in provinces with extensive sugarcane farming that were hit harder than previously reported.

Thanawut Norath, a technician at the Regional Environment Office 10 in Khon Kaen, inspects one of the six air quality monitoring stations in the province.

In February and March, Khon Kaen’s environmental office recorded air pollution hotspots based on satellite images in several Isaan provinces like Kalasin, Chaiyaphum, Maha Sarakham and Roi Et. Especially Nong Bua Lamphu and Udon Thani, two provinces with large sugarcane areas, appeared dark red on the maps.

Many of the country’s stations are not equipped to record the most dangerous type of pollution known as PM2.5. These microscopic dust particles are a byproduct of burning that commonly come from power plants, incinerators, car exhaust, wildfires and agricultural burning.

Less than 2.5 microns in diameter, or one-thirtieth the size of a human hair, the airborne particles are particularly harmful to human health. They can cause asthma and respiratory inflammation, and increase the risk for lung cancer, heart attack and stroke.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated last year that about seven million people worldwide die from the effects of fine dust particles in polluted air every year. The vast majority of premature deaths linked to air pollution occur in low- and middle-income countries like Thailand.

But the six air quality monitoring stations in Khon Kaen (of which only one can read PM2.5 pollutants) can not pick up any accurate readings of pollution in nearby provinces, and the exact scale of the problem remains unclear (see Part X of our series on Sweetness & Power: “Isaan will be choking on toxic air again soon. What to do about it?”).

“We should have air quality monitoring stations in every province but this would require a large budget,” says Virunphop Suphap, director of the Regional Environment Office 10 in Khon Kaen.

Thailand currently has 66 full-fledged air quality monitoring stations, most of them located in Bangkok, the Central region, the North and the Deep South. Only three (and possibly a fourth in Ubon Ratchathani) of the twelve monitoring stations in the Northeast are full-fledged stations capable of reading PM2.5 and PM10. There are also some mobile air monitors in use.

A full-fledged air quality monitoring station costs at least 10 million baht (about $327,000 USD) and annual maintenance cost stand at several hundred-thousand baht, according to Virunphop. Mobile units come with a cheaper price tag.

Virunphop Suphap, director of the Regional Environment Office 10 in Khon Kaen, demonstrates the use of a portable air quality monitoring device. The office is currently looking to buy another ten units.

A sweet source of air pollution

According to data of the past fours years from Khon Kaen’s environmental office, the concentration of PM2.5 tends to peak beyond standard levels in the months of February and March.

Virunphop explained that the most prominent source in Northeast for the tiny dust particles is agricultural burning, especially sugarcane fields and rice straw. Air pressure also affects the build-up of pollution levels. During high pressure, the air is usually still which keeps pollutants from being dispersed, and without rain they remain longer in the atmosphere.

Haze floating across the border from neighboring countries often makes the situation worse.

Agricultural burning is common in the Northeast as the region produces the largest share of Thailand’s sugarcane–46 percent in 2018 according to data from the Office of the Cane and Sugar Board (OCSB).

More than five million rai of farmland (800,000 hectares) in Isaan is used for sugarcane growing. The largest sugarcane-producing provinces are Udon Thani (711,900 rai), Nakhon Ratchasima (672,952 rai), Khon Kaen (650,196 rai), Chaiyaphum (616,639 rai), Kalasin (432,111 rai), and Nong Bua Lamphu (315,706 rai), according to the OCSB.

Sugarcane cultivation is most highly concentrated in Nong Bua Lamphu where 13.1 percent of the province’s total area is grown in sugarcane. The OCSB’s 10-year plan foresees an increase of 53 percent of sugarcane fields in Thailand by 2024, an increase of 5.57 million rai (891,200 hectare) to 16.1 million rai (2,560,000 hectare).

Two-thirds of Isaan’s sugarcane farmers are small landholders who are more likely than large growers to resort to burning their fields before the harvest to save on labor costs.

Last year, the price for sugarcane dropped to 450 baht per ton ($14.70 USD) from 800 baht per ton ($26.16 USD) the year before, according to Mana Muangkhun, president of a community organization in Nong Bua Lamphu. Many sugarcane farmers chose to burn their fields to make harvesting easier and less expensive.

“When the harvest season started around November, this area was full of thick soot in the air,” Mana recalls.

The burning of sugarcane is a major source of air pollution in the Northeast. The practice is hard to police and pollution control officials in Khon Kaen want sugarcane mills to pressure their growers to refrain from burning their fields.

Not just a spell of bad air

With the government pushing for a massive expansion of sugarcane in the next years, the burning of the fields is likely to become more frequent as seasonal air quality in the Northeast will worsen.

The OSCB estimates that while burning of sugarcane will become less frequent in the North, it is on the rise in the Central region and in the Northeast.

Dr Patiwat Littidej, head of the Geo-Informatics Research Unit at Mahasarakham University, believes that the region is heading towards an even more severe air pollution crisis. [Read an op-ed on this topic here]

Dr Patiwat predicts that the concentration of PM10 and PM2.5 will become more intense as sugarcane cultivation–and sugarcane burning–increases to feed the sugar mills according to the government plan.

He suggests to address the issue by creating a dedicated agricultural output monitoring system to control the burning.

Dr Patiwat also suggests the government could install minor air pollution control stations that provide sufficiently accurate data but have a lower purchase price.

Khon Kaen’s environmental office is working on plan with the Federation of Provincial Industries to collaborate with sugar companies like Mitr Phol to solve the problem and prevent farmers from burning their fields.

Making the invisible visible

But to tackle air pollution and keep the population informed, real-time air-quality monitoring in all provinces is critical, argues Chariya Senpong, Climate and Energy Campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

“Air pollution monitoring stations in all areas is the most effective way to solve the problem,” Chariya says.

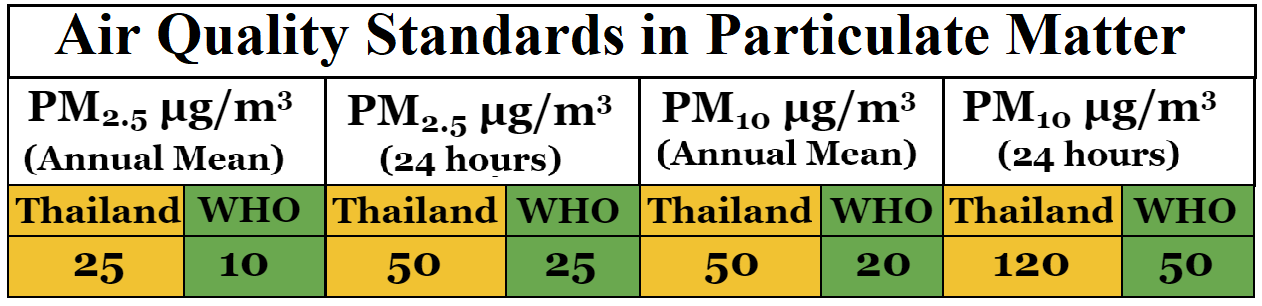

Chariya also calls on the Pollution Control Department (PCD) to bring their air pollution norms in line with international standards. Thailand’s air quality standards are considered weak with PM2.5 standards (annual mean) being 2.5 times higher than what’s recommended by the WHO.

Director-General of the PCD Pralong Damronthai told The Isaan Record that the agency would soon begin to follow the air quality standards of the WHO or European countries. He promised to start bolstering the air-quality control system in Isaan this year.

“This year, the PCD got funding from the central budget,” he said. “We will install air quality monitoring stations in three more provinces in northern and southern Isaan.”

Burning season begins again in Isaan

Farmers will begin burning their sugarcane fields next month. That’s worrying for health officials in those Isaan provinces where there’s a lot of sugarcane grown but no monitoring stations. With no official monitoring, there’ll be no official air pollution warnings from the government.

In the meantime, local hospitals will have to depend on themselves to find information on air quality so they can properly counsel their patients–and themselves.

The young dentist Apichat Suvannasing at the local government hospital in Nong Bua Lamphu is worried given how sick he’d become earlier this year.

But at least he’s glad that he’ll know what he’s breathing–a doctor donated a portable air quality monitor to the hospital and he’s been able to track the area’s air quality.

That’s some consolation to him as he prepares for a new seven-month bout of coughing.