I’m Lao. So what? You’re so damn Thai!

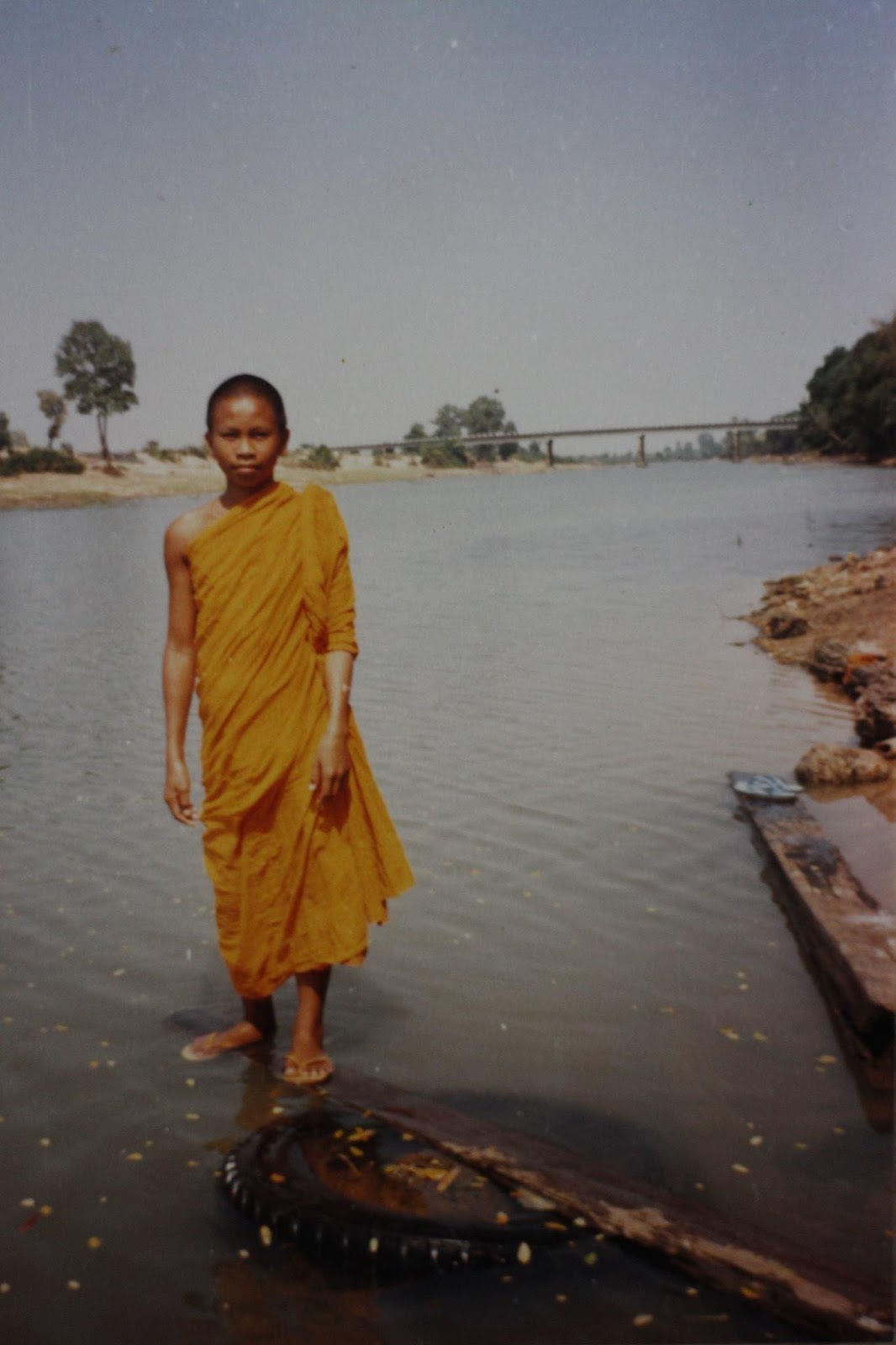

Isaan people have long been discriminated against, not only by regular people but also by the religious world. Ubon Ratchathani University professor Tee Anmai recounts his experience as a novice from Isaan when he was called “Lao” and rejected by Bangkok temples.

By Tee Anmai

Twenty years ago, I was on a bus. The bus was packed as it was rush hour. People were coming from work and school. A group of four or five school boys were jammed right next to me. Eavesdropping on their boyish rowdy conversation somehow helped my mind drift from the misery of the traffic jam. However, I was snapped back into reality upon hearing what they were saying.

“That’s…so damn like a yokel.”

“Yeah, freaking bumpkin clothes.”

“So damn Lao! Hahaha.”

I turned to them, unamused, and blurted out, “Lao and so what?!” They were frozen. Their smiles faded. Then they moved away from me, squeezing into the crowd at the other end of the bus. The bus went silent, without those loud and crude conversations from the teens. Instead, the voices inside my head kept getting louder and louder.

I was thinking back to about 30 years ago. I, as a rural farm boy from the middle of nowhere, was able to get a higher education than primary school thanks to a summer novice ordination program.

After three years, I graduated middle school at Wat Pho Pruksaram in Tha Tum, Surin province. I figured, if I wanted to pursue high school and all the way to university, I’d have to do it while wearing those yellow robes, just like how some of more senior novices had done before. I then struggled my way to Bangkok to take an admission test to the Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University of Wat Mahathat Yuwaratrangsarit, located near Tha Phra Chan pier.

It turned out that the test wasn’t as difficult as finding a temple in Bangkok that would accept me.

I was a novice who hadn’t passed the third level in the Pali exam, and that already limited a lot of my options. Worse, I was a novice who came from the Northeast. It was that fact that put me through a great ordeal.

“A Lao novice, huh?” That was the question I always heard Bangkok monks or abbots ask of little novices from the Northeast. It was equal to a rejection of the request to join the monastery.

My test result came out. I was accepted to Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya. However, I didn’t have an address. None of the temples would receive me.

The words “Lao novice,” uttered by Bangkok monks, was an unconscious, automatic response that resulted in discrimination. If you ask how I felt back then, I just thought: “I’m Lao and so what?”

In my rural hometown, we’d normally say: “That’s a Khmer from Ban Thanope.” “That’s a Kuy mahout from Ban Kraphotha Klang.” “That’s a Lao from Ban Suakwoek Phon Tum.” But these were just descriptions, an introduction to a person and where they were from. They weren’t slurs with an intention to discriminate against anyone.

During my entire three years of high school, my name remained registered under Wat Pho back in Surin. With no temple to take me in, I had to stay out on a balcony off of a monk’s quarters at Wat Makkasan. The room belonged to a monk from Surin who was kind enough to share his space with me. I had to sleep, study, and do my homework under the sun and in the rain and wind on that balcony.

Sometimes, my father would come and visit me at this temple. I had to lie to him and say I shared the quarters with this monk, but would move out and sleep onto the balcony just for the time when the monk wasn’t there.

It wasn’t until more than a decade later, after I’d gotten a job, that my father learned the truth. He said, “My son, what a harrowing time you had to go through.”

Lao people along the Mekong and in the Chi-Mun river basin have long been looked down upon and suppressed by Bangkok people living in the Chao Phraya basin. It’s not only the case in the secular world, but in the religious world as well.

During my time as a novice in Bangkok, I always heard students at Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya say it would be extremely difficult for an Isaan monk to pass the ninth level of the Pali exam — the highest in the system. They also said it would be impossible for a monk from the Northeast to become the Supreme Patriarch. The case of Phra Phimoldhamma (Art Asapho), a distinguished monk from Khon Kaen who was arrested and incarcerated over communist charges in the 1960s, was always brought up as an example.

Several days ago, my friend, a dentist in Khon Kaen, sent me about five or six audio clips of someone slandering Isaan people on the social app Clubhouse.

I couldn’t listen through any of them because I was so filled with anger and hatred.

Trying to calm down my friend, I said it was just part of the military-led Information Operations. But I was fully aware it was not. Rather, it was an expression of the deep-seated impulse of the Thais who relish looking down upon and discriminating against others.

Look at the school textbooks for our students nowadays. Who was an ally of our country? They were all enemies. It is all about tooting our own horns and smearing the reputations of others. Stories surrounding this country are a history of pain and trauma, full of invaders and slaughterers, no neighborly neighbors. The Burmese torched Ayutthaya. Thao Suranari battled the Lao from Vientiane. However, our history textbooks barely even mention that the Emerald Buddha at the Grand Palace was actually stolen from Laos, after the Thais burned down the temple where it was originally housed.

Regionally, Thailand discriminates against its neighbors as well. It belittles the neighbors like it naturally would as a minor colonizer of the lower Mekong basin. Even within the country, Thailand has always been a colonizer. This nation was built up by aristocrats from Bangkok who were sent out to topple provincial leaders and seize power from them. (They’ve loved staging coups for over a hundred years). They force their identities upon others, practice cultural hegemony, and marginalize local customs. They have no place for diversity and compromise. That’s why we abuse and stomp upon others’ human dignity.

Crudeness is everywhere, whether on the state administrative level (both secular and religious) or on a social level. It’s “Thainess” that’s the problem. Otherwise, that ill-advised, foolish Clubhouse session wouldn’t have happened at all.

So, if someone branded me as being “so damn Thai,” I’d really have to deeply reevaluate myself.

Note: The original version, written in both Thai and Lao with Thai script, was published on Nov. 12, 2021.