This editorial provides an analysis of the 2015 Draft Constitution using the unofficial English translation here. The Thai version is available here.

GUEST EDITORIAL by John Draper

In the draft constitution, there is no explicit mention of minorities or minority rights, making this constitution the only one in ASEAN to not have a provision for such rights. In addition, Thai is not specified in the constitution as the national language, meaning there is no recognition of other languages, nor a framework for supporting minorities along ethnolinguistic lines.

Together, these omissions make the proposed Thai constitution the most backwards in ASEAN and the one least compliant with treaty obligations in the area of linguistic human rights, namely the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, all of which have been ratified by Thailand.

In the Northeast, this affects approximately 18 indigenous ethnicities, primarily the Thai-Lao, the Northern Khmer, the Khorat, and the Phu Thai, as well as several million integrated Thai-Chinese.

Using standard predictions of language death rates proposed by a leading authority on language, David Crystal, it is likely that all those ethnolinguistic groups with populations of less than 500,000—all but a handful in the Northeast—will experience the erasure of the language aspect of their identities by 2100. This basically means that while the song forms of these minorities may survive into the next century, their children will not understand those songs. This represents a massive loss of Thai cultural heritage in the Northeast.

Section 5 of the constitution includes the standard provisions against discrimination based on race : “The Thai people, irrespective of their origins, sexes or religions, shall enjoy equal protection under this Constitution.” Also under the heading of “Human Rights,” Section 34 states: “Unjust discrimination against a person on the grounds of the difference in origin, race, language, sex, gender, age, disability, physical or health condition, personal status, economic or social standing, religious belief, education or training, or constitutionally political view shall not be made.”

However, there is passing mention of the concept of ethnicity. Chapter 2: Directive Principles of Fundamental State Policies, mentions, in Section 83 (5): “The State shall strengthen local community in the following matters…: (5) protection of indigenous and ethnic groups to maintain their identities with dignity.”

While such recognition is an advance on the former constitution in terms of specificity, it has essentially been the position of the National Economic and Social Development Board in its five-year plans as implemented by state ministries such as the Ministries of Education and of Culture for the past 15 years.

In terms of how this applies to the Northeast, it should be noted that the Thai state in the past has admirably tackled the issue of race in the region – on paper. Its 2011 report to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination under the UN International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, available here, is remarkably enlightened. Building on Mahidol University’s 2005 Ethnolinguistic Map of Thailand project, it declares Thailand to be a multi-ethnic, pluralistic country and acknowledges the existence of 62 ethnic groups in Thailand, belonging to five language families.

In an approach informed by the latest research and detailing the state’s evolution of the understanding of the ethnic issue since the 1990s, it first lists and describes in detail three main ethnic groups in Thailand: the mountain peoples or “Persons on the Highland,” the “Sea Gypsies,” and the “Malayu-descended Thais.”

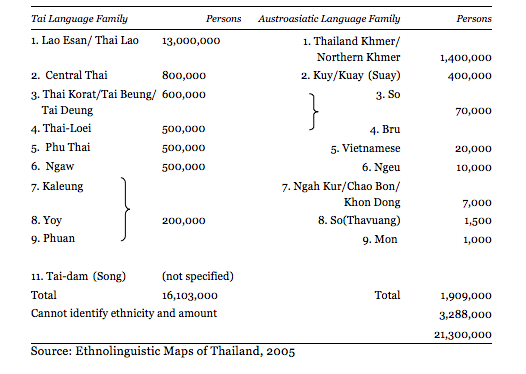

It then describes a fourth group, “other ethnic groups,” under the heading “Ethnic Groups in the Northeast,” with a detailed table listing all the ethnic groups in the Northeast except for Thai-Chinese. This is reproduced below:

Table 3: No. of Ethnic Group Population in the Northeast (Esan) by Language Family Group

Crucially, the Thai Lao identity is recognized in this 2011 report for the UN Committee in a way not seen outside academic circles and in doing so undoes nearly a century of the systematic erasure of the largest minority identity in Thailand. This erasure, via a program of assimilation, began in the late 19th century with the consolidation and annexation of the Khorat Plateau and was accelerated in the 1939-1942 hyper nationalism-driven 12 State Cultural Mandates which changed the name of Siam to Thailand, made Thai the national language, and disappeared by diktat all the minority identities in Thailand. The historical treatment of the Thai Lao and their crucial importance to understanding Thai political development, including in the Thaksin era, has recently been highlighted in the English-speaking public sphere by the anthropologist Charles F. Keyes.

The 2011 report’s description of the situation in the Northeast is sympathetic to the problems of the region’s other minorities. In particular, the Kuy, Yogun and Bru are mentioned as facing extinction.

However, the description regarding the relationships between the peoples of the Northeast is somewhat unusual, “Even though there are diverse ethnic groups in the Esan region… due to the generosity and kind-heartedness of the Esan people in general, as well as their experience of interrelating with people of diverse ethnicities, the Esan people of different ethnic groups mingle well and always welcome people from other places. This background is like a special force that unites them and creates a drive for them to relate more with people in the other regions.”

Nonetheless, submitted as it was in 2011, it completely overlooks Thai-Thai Lao interactions, including widespread destruction in the Northeast in May 2010, mainly focusing on violence against symbols of Thai national rule, including the arson of provincial administrative halls. Indeed, it might be argued that the prevention of additional ethno-political violence in May 2014 was one of the unstated reasons which drove the Thai military to intervene in its May 22 coup.

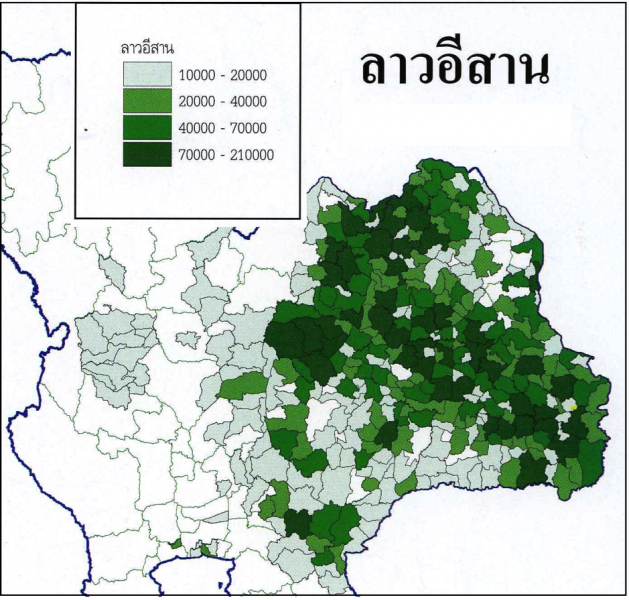

Speakers of Lao Isaan, adapted from Ethnolinguistic Maps of Thailand, Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University, 2005

The draft constitution of 2015 is obviously a retrograde step compared to the progressively-minded report to the UN committee combatting racism. It ignores the more normative constitutions of its neighbors regarding minority rights; is apparently oblivious to the pattern of pluralistic progress put in place since the 1997 Constitution and developed in partnership between major Thai universities, UN organs such as UNESCO and UNICEF, as well as indigenous organizations themselves such as the Tribal Assembly of Thailand and the Inter Mountain Peoples Education and Culture in Thailand Association; and it overlooks its treaty obligations.

Thailand cannot portray itself as a pluralistic country in its reports to supra-national organizations such as the United Nations while failing to put in place organic legislation or at least constitutional safeguards to support minority ethnolinguistic rights, such as the stalled draft of National Language Policy. Nor can it, according to its own draft constitution, grant any measure of autonomy to the Thai Malayu, who now exercise limited elements of Sharia law in the three southern provinces collectively named the Deep South, without providing for autonomy for the Thai Lao and other major minorities such as the six million Khon Mueang of the North.

The discrepancy between the “Thainess” of the draft constitution and the hard-won scientifically-based developments in Thai academia, Thai concepts of pluralism, and Thai understanding of their own history as embodied in the 2011 report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, is obvious. It represents a massive reality gap between how radical conservative elements of Thailand’s socio-political spectrum portray the country to its own people in local media and how Thailand could—and still can—develop itself in this crucial field of minority rights in partnership with the international community.

Thailand cannot continue to dumb down its own population and aim to assimilate rather than integrate and equalize. Further, in recent high-level support for the concept of pan-Thainess based on pseudoscience it risks more than becoming a pariah state; it invokes a specter of xenophobia and the march to authoritarianism buoyed by the chauvinism, which harbors the conceit of the natural leadership of a superior race.

The draft constitution suggests valuable political reforms and is a major intellectual work in its own right. While the promise of reconciliation is there, its inward-looking nature and the lack of any appreciation for minority rights will be its own undoing in the years to come unless it is itself reformed as a matter of urgency.

Postscript

After having read this article, you may at first see the Thai military as the “bad guys.” This would, however, be to fall into the trap of dualism. The Thai military developed Thainess through the filters of British imperialism, French colonialism, Italian fascism, and German Nazism, as well as the bushido concept and Japanese imperialism. More recently, their institutional memory includes some of the worst forms of counter-insurgency and psychological warfare imaginable, acquired during the dirty wars of the Cold War period. And most recently, fourth generation warfare and the technology that facilitates the surveillance state have informed Thai military thinking.

One result of this mentality is that the study of Chakri-period dynastic history in Thailand has been criminalized through the lese majéste laws, seemingly against the wishes of those the law would seek to protect. This death of history – a history dominated by the interactions of an absolute monarchy (and now a strong form of constitutional monarchy) with peoples now minorities in Thailand – has supported processes of assimilation rather than equalization. All this has been documented in the academic literature, a literature that cannot in its entirety be read or studied in Thailand.

Still, the Thai military is not “the enemy”. It is a product of a system and consists of individuals, ones that does not necessarily understand why it is a tragedy that many Thai Lao children reject the “Lao” part of their identity nor why it is a tragedy that the majority of Thai Lao children’s cultural identity has been erased to the extent that they do not know they used to have a civilization including a rich literary heritage. In the quest to portray Thailand as a utopia of Thainess, those in the Thai military may not understand these tragedies because the study of history in Thailand has been turned into a pseudo-science and because the study of its sister science, philosophy, is not promoted as part of a holistic education.

You may, on having read the article, feel that what has happened and that what is happening in Thailand constitutes a crime – a crime against humanity. You would not be alone. Cultural genocide was written into the draft Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and removed at the last moment because of the sensitivities of the period and of the crime itself. Alternative names for what is happening in Thailand, known to some reading this introduction, are ethnocide and linguicide.

This does not mean the Thai military is guilty of a crime. The Nuremberg Trials essentially made the point that individuals are guilty of crimes, not peoples or institutions. And, those of you who are familiar with Buddhism know that it teaches absolute compassion for the human condition. In fact, individuals in the Thai military, as epitomized by General Prayut, appear to be desperately engaged in a war on endemic, embedded corruption in the Thai polity in bid to stave off sanctions by the West due to the appalling crimes against human rights taking place in Thailand every minute of every hour of every day, including the trafficking and slavery of minority children.

In this bid, the Thai military as an institution is also taking on the “cleaning house” of an entire country. General Prayut himself, and in some ways the whole socio-political system, have been demonstrating signs of increasing cognitive dissonance due to the enormity of this task of attempting to purge corruption from one of the world’s most corrupt states. Thailand is corrupt if only because of the accidents of history, its geographical position and the size of its population. But, the underlying psychology of Thai client-patronage networks which support corruption existing within a social system prioritizing Buddhist values and thereby rejecting materialism and promoting a path towards goodness also creates such a dissonance. Still, the pervasive extent of political, bureaucratic, police and military corruption is perhaps only just being appreciated by the Thai establishment, which seeks to promote such goodness.

In the words of a Thai metaphor, the eyes of some in the Thai military are likely only now, because they have sought to implement broad reforms not seen in a generation, being brightened regarding the massive task before them. This may be a sudden psychological shock for some of them. On issues such as slavery in the fishing industry, on forest reform, on education, and even on the pricing of lottery tickets, the Thai military seems both exasperated and at a loss. For this, in the Buddhist tradition, they deserve compassion.

If you understand and agree with the basic premises in this postscript and sympathize with the sentiments expressed in the article above, you may feel a moral obligation to help those determined to spread and develop a Thainess based on the fundamental premise of a multi-ethnic state which recognizes the reality of both triumphs and tragedies in Thailand’s own history – one that cannot at present be argued for by Thai ethnic groups because of the overwhelming discourse of pan-Thaism currently being produced by the Thai military. Furthermore, in the ultimate tragedy, the majority of these minorities not only do not know – cannot know – their own histories, they do not know they have rights under treaties like the one mentioned in the article.

If, after reading the article, you do want to help, please post it to lists, to websites, to Facebook, and to friends and colleagues via email. Requests to post the article to websites should be directed to the original copyright owner, The Isaan Record (editor@theisaanrecord.co). The Thai military needs to be helped to understand that there is an alternative future for Thailand which does not rest upon rejecting a model constructed of both pluralism and of individual rights and responsibilities in favor of totalitarian authoritarianism. It needs to understand the draft constitution must be amended to include minority rights, and it needs to understand why.

John Draper is a project manager with the Isan Culture Maintenance and Revitalization Programme at the College of Local Administration at Khon Kaen University and writes for the Khon Kaen School.