Guest contribution by Mike Eckel

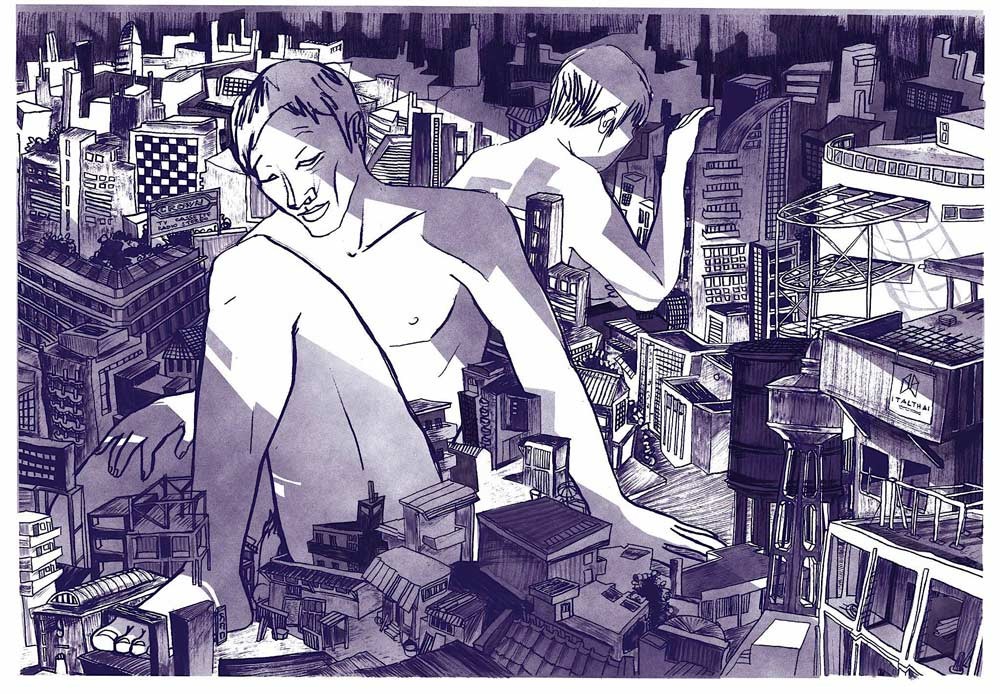

From 6 October to 26 October, an abandoned building in Khon Kaen city hosted an art show, atypical and unprecedented in Thailand’s art scene. Khon Kaen Manifesto gathered artists from Isaan and across the country, drawing a similar spread of observers. The art was bold, subversive, radical, and honest. It left observers hanging with questions about their society, politics, history, and culture, and a feeling of interrupted silence.

Artists were given an empty space in a building never touched by or intended for art. The canvas spanned over six floors of a planned financial building, old and crumbling, that never met its use. The business tanked in the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s, leaving behind a concrete monument of a failed vision. Today, the ruin stands for Thailand’s overzealous method for a reaching a brighter future, and it provided the perfect stage for artists to express the ideas behind Khon Kaen Manifesto.

Thanom Chapakdee, Manifesto’s head curator and visionary, is a recently retired professor of art at Srinakharinwirot University, and one of Thailand’s most respected and feared art critics. When artists receive Thanom’s approval, it signals their work is among the best in the country. But many of Manifesto’s contributing artists were peripheral to Thailand’s art scene, and to society at large. Thanom wanted the art festival to “abandon the palace” of Thai social institutions. In an interview with The Isaan Record, he argued “art is democracy.” Rather than conforming, art should be free to any source of expression. The Thai graffitied (above), “liberty is humanity,” fits well with this ideal. The festival provided a rare acceptance in Thai art of democratic expression and countered a dominant discourse that condemns peripheral narratives as illegitimate and unworthy of respect. Thanom told artists that they can do whatever they pleased, both in their work and how they used the space. There were no limitations to the artists’ imaginations.

In the entrance of Manifesto, a wall covered with the event poster that has an Isaan phrase bolded in the middle, liam map map, meaning to gleam brightly. It referring to the rhetoric of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, the infamous military dictator whose political career has become synonymous with the development of Isaan in the 1950s and 60s. Liam map map emerged at that time to mock Sarit’s vision for Khon Kaen, which he believed could one day gleam brightly with the infrastructure of modernity. The artwork of Khon Kaen Manifesto addressed Sarit’s vision for the city’s development, which he infused into Thailand’s first national development plan.

Created by Anurak Khotchomphu, this artwork replicates a map of Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Its blueprint was originally created by Sarit in the Cold War era, intended to mark communist “danger” zones where communism existed or could spread. The seared territory above Khon Kaen is the Isaan region, which, during that period, offered forest protection for communist insurrection groups. Sarit’s paranoia of Isaan falling completely to the communist insurrection provoked his fierce campaign to capitalize and develop the region. The region’s association with communism seared an image of radicalism and a sentiment of mistrust of Isaan people into Thailand’s modern political consciousness.

Artist Woraphan Intaraworopad filled a room with scenes of paper-mache skeletons and ghosts. According to Nibhon Khankaew, a Khon Kaen based art teacher [Read our interview with Nibhon here], and Thanom’s vice curator and organizer, the artwork refers to the so-called Red Barrel Killings. In 1972, the Thai military massacred civilians in Lam Sai District, Phatthalung Province accused of being communists by burning them in red barrels. The official accounts recorded 200 people were killed. But local accounts estimate up to 3,000. According to Nibhon, the military blamed these killing on the Widow Ghost or pee mae mai, a common Isaan folktale in which cheating men are killed by a ghost widow.

Pridi Phanomyong, to the left, was a main instigator and leader of Siam’s 1932 coup that formally overthrew the absolute monarchy. He was driven into exile in China in 1949. Chit Phumisak, to the right, once a writer, thinker, and philologist. He was jailed by Sarit for his politically subversive writings in 1957. In 1965, he joined the Communist Party of Thailand in Sakon Nakhon and quickly rose as a leader. But in 1966 Chit met his death by murder, executed for his political standings. When Manifesto first opened the other wall displayed a painting of Jatupat Boonpattararaksa, Pai, the leader of the student activist group Dao Din. According to Thanom, security officers came within the first week and asked curators to remove any piece related to the activist, or any works alluding to lese majeste. Pai is currently serving his last year of a two-and-half-year jail sentence for royal defamation. Observers who saw the uncensored artwork left with the lingering question: how is Pai carrying on the legacy of Pridi and Chit as a political figure and image? Artist Sermsilp Pairin drew an obvious line between the two and the student activist, being a contemporary symbol of resistance and protest. Those who came after the military censorship were left with the question: what irony there is in the military’s asking his face to be removed, as many decades earlier Chit and Pridi were removed for the political threat their presence evoked.

According to Nibhon, after the military visited the exhibition, he and other curators decided to “turn down the temperature.” Any piece related to the military coup, lese majeste, or Pai Dao Din was defaced or removed. But the defilements did not divert the artworks’ intention. Rather, it covered aspects directly related to what was deemed off-limits, leaving observers evermore drawn to the central message. This piece by the Guerilla Boyz, an anonymous group of contemporary spray paint artists who claim to express their work without form, depicts Sarit passing a baton to Thailand’s current dictator, General Prayuth.

As captured by Pongsak Raknarong, the iconic mask of those who drive Thailand’s agricultural production for a compensation of cyclical misrepresentation and indebtedness. To the right, the expression of villagers at their emotional limits while protesting their local administration. Following the overarching narrative of Manifesto, photos were posted of those who weave the narrative of history, protest, and oppression for those caught in Thailand’s periphery.

Being an unprohibited space, pieces flowed together and overlapped, physically and in theme. “Even the air cannot pass through,” poet Koh Sa Ga Ri Ya Amata painted in the days Manifesto first opened. Koh confronted through this and other contributions the killings of muslims in the Tak Bai Incident of October 25, 2004, including a simple piece of paper with the name of every person killed in these conflicts. Below, posted days later, sits a Shan women painted to resemble The Mona Lisa. This symbolizes the Shan identity as something deserving due legitimacy to Western identities. The Shan State in Myanmar was long locked into a civil war with the Burmese military, fighting for its autonomy. Many Shan people still proclaim their independence and right for statehood. Related yet unplanned pleas throughout Manifesto weaved into uniform themes, in the above case calling for the recognition of Shan peoples’ yearning for sovereignty and Muslims’ struggle to become equal members of Thai society.

The pieces of Khon Kaen Manifesto collectively protested forces which silence, belittle, or eradicate those who champion rights and democracy in Thailand. One of those forces is the Thai education system, which enforces strict rules on dress, speech, and behavior. Thai children have to keep their hair in a uniform, gender-defined style. Any deviation from these rules risk physical punishment or forced social humiliation. In regard to political expression, many youth feel apathetic about politics or remain fearfully silent. Four indistinct students, facing a wall, represent both the uniform mass that Thai students embrace and their apparent voicelessness.

“Thai people on average are drowning in 1.78 million baht of debt.” While much of Manifesto protested political and social issues within Thailand, some also critiqued economic issues. Through this news clip, Janvit Suthannasirichai shed light on a paralyzing reality for the majority of Thais: average household debt grips families and individuals with millions of baht, totaling 78.3% of Thailand’s GDP in the third quarter of 2018. Today many rural poor throughout Isaan are caught in a vicious cycle between borrowing and spending. Linking this piece to Manifesto’s themes raised the question for observers: How did Sarit’s vision of development, and how will Prayuth’s current 20-year strategic plan, impoverish and marginalize Isaan’s poor?

Thanomsak Chaiyakham is a sculpture artist local to Khon Kaen. His work is a statement about the lack of balance in economic power throughout Thai society. The arch represents that economic arch over society, as pieces crumble and scatter on the ground due to its weak construction. Thanomsak explores how the economic and who it serves.

On the third floor sat an empty room with a chair, hanging upside-down from a noose…Scared into Thai society’s consciousness is that bloody massacre of 6 October 1976; here, symbolized noose and chair. An indistinct classroom-like chair, a blunt instrument of state persecution, used to bash the corpse of a hung student protester. The most emotionally rupturing piece of Manifesto. Artist Nutdanai Jitbunjong intended the piece to be subtle. And for many it was. The entrance stamp was of the chair. Space was left to expose the lacking awareness of the events of 6 October.

Eighteen faces painted bloody and with a translucent aesthetic that evokes the feeling of a ghostly memory. On 10 April, 2010, after months of a protest in the heart of Bangkok’s shopping district, soldiers dissolved the red shirt protesters by gunfire. These are the faces of those protesters and civilians killed in the clash. Artist Tawan Wuttaya is based in Bangkok, and known widely for his politically controversial watercolor and oil-based paintings. His work often depicts political leaders with a ghastly aesthetic, or victims of political violence with a painful expression of their suffering.

A white cloaked figure meeting the emptiness between water and sky, looking out to the Gulf of Thailand. The artist, Ampannee Satoh, is a Muslim living in Southern Thailand. Her work shows people in black and white standing in spaces, as made to look displaced. It evokes the feeling of emptiness, isolation, and the otherness experienced by migrants and minorities in Thailand, especially that felt by the Muslim minority.

Artists were free to collaborate, use the space as they pleased, and seek inspiration from the works of others. Curators were keen on the concept that art spaces do not solely belong to one person; the art should break the chains of Thailand’s hierarchies and an affinity towards status favoritism and corruption. The lines which allude to an image of a cage were set on this wall long before Manifesto. The artist Tongthat Theparukartists saw a logo with the letter tho thahan around Manifesto’s main site, thus inspiring the signature seen at the bottom this and each piece he presented at the exhibition. He created a story out of this symbol with black, red, and white birds.

Peeking through a broken wall, one saw a network of laced red plastic being physically weighed down by an iconic image: the Thai constitution. Khon Kaen University art student, Sermsilp Pairins, displayed this piece to communicate frustration with the Thai state’s efforts to oppress democratic resistance to the coup. Anchored by today’s military constitution, the webbing represents that which collectively fights the institutions which preserve and uphold the military’s constitutional law and governance.

A fist, nose, and veins of golden blood. Chokchai Pakpho leads observers to questions concerning the environment, politics, nature, and livelihood. Typically, his pieces are intentionally left open to interpretation. However, in this piece, he offered curators one clue: the veins represent the Chi and Mun rivers feed Ubon Ratchathani, Chokchai’s home province. The meaning behind the fist, nose, style and drama is left to be conjured up by the observer. Curator Nibhon suggested the fist could represent a dam–the Rasi Salai dam along the Mun river that displaced people from 500,000 rai of land. Even now locals continue to oppose the dam and many still are waiting to be compensated for land loss. The fist could also represent the fight against the military government, without surrender, Nibhon suggested. One could also see the fist as an iconic symbol of resistance…or something entirely different.

The final week of Manifesto saw waves of taggers, including local teenagers and Khon Kaen University students. Lead curator Thanom said that although they plan to host another Manifesto in two years, this building will not be used again for a formal exhibition. All temporary pieces were removed the few days following Manifesto’s closing. Ironically, the physical evidence that remains is the most local, and democratic art–that which was uncurated, uninhibited, and expressed the thoughts, creativity and passion of those most intimate to the canvas.

Head curator Thanom Chapakdee intended for the art festival to inspire a paradigm shift in Thai art. The event was not held in a formal gallery; it simply brought a new purpose to a lost space. Khon Kaen Manifesto showed art can be held at any local level–cities, districts, and villages.

The building now sits locked and empty. The questions this unlikely art festival raised are left hanging. The onus of carrying on its importance is now on the observer.

The art of Khon Kaen Manifesto was bold, empowering, and honest. The artworks were unprecedentedly radical and thus controversial, however consciously so. The festival gave artists a space to liberate their hidden narratives and manifest them as a creative physical expression. Most significantly, it accepted their peripheral narratives as legitimate in the face of a cultural dominance by Thailand’s elite. If “art is democracy,” a radical narrative erupts when the chains of expression are broken.