Before her is a shrine decorated in bright fabrics of gold and silver, floral arrangements, and tiger figurines. Offerings of flowers, soda, alcohol, incense, candles, cigarettes, and betel nuts have been laid before her, as an invitation for the spirit.

Once the ritual preparations are complete, the ten people seated around in the upstairs room burst out in rhythmic chant. Their voices sing out into the humid night air, calling out to the spirits that live in the surrounding forest.

The woman known as Lamyong Trairat undergoes a transformation.

With cigarette in hand and betel nut stuffed in her mouth, Lamyong’s voice booms out in a harsh raspy tone, the red betel juice dripping. The voice is no longer hers.

It is the voice of Pho Phra Ked, one of the hundreds of spirits that lives in the Dong Phu Din forest in Rasi Salai in Sisaket Province, known as “the capital city of spirits.”

For over three centuries the villagers of Rasi Salai have connected with these ancient forest spirits through ceremony and tradition. The villagers and spirits use this ancient bond to unite through shared adversity in protest against development projects, most famously the Rasi Salai dam, threatening their land and livelihoods.

Guest contribution by Cora Walsh

Lamyong became a medium at the age of 29. When possessed, she feels like air is coming out of her ears; she feels seasick, and has no control over her speech or movements.

Loving the land

The land and waters of Rasi Salai are inextricably bound to villagers’ way of life, culture, and spiritual beliefs. For generations they have depended on the Mun River and surrounding wetlands to sustain themselves.

Like a natural supermarket, the Mun river and wetlands supply the villagers with a wide variety produce: wild rice, vegetables, crabs, fish, mushrooms–almost anything they could ever need–for free.

The villagers’ faith in the Chao Pho Dong Phu Din spirits and their relationship to the land are deeply intertwined. They believe Chao Pho to be the protector of the land and their lives.

“We believe there is a spirit for each element of nature. Spirits for the soil, spirits for the water. There is one guardian, Chao Pho, that watches over all the spirits of nature,” says Boon Wangpew, a local farmer.

Medium Lamyong as spirit Pho Phra Ked in the little attic preaching about the forest and people.

The villagers play an important role in protecting the environment and the spirits of Chao Pho. It is believed throughout the community that if someone harms nature, or takes from the land without asking permission from Chao Pho, then the spirits will punish them with injury or illness.

“Even if you take something small like mushrooms or flowers, you need to ask permission or you might experience something bad or get lost in the forest,” says Boon.

Before they harvest their fields, go fishing, or gather vegetables from the wetlands, villagers pray to Chao Pho for permission to take from the land.

“The people here really respect the spirits in the area before they plant rice. Before they start doing agriculture, they will pay respect to the spirits. They respect the animals and the plants here. They try not to kill any plants, even the small plants,” says the spirit of Pho Phra Ked.

These feelings of fear and respect for the spirits helps with community accountability for keeping the land clean and healthy. “All the people are guardians of Chao Pho,” says Boon.

The great ceremony

To honor and respect the spirits of Chao Pho as a community, the people of Rasi Salai come together twice a year during a ceremony called buang suang chao pho dong phu din.

Spirits now in their mediums, including Pho Phra Ked (with right are outstretched), assemble before Ya Pho Yai, king of the spirits (dressed in all white) during the buang suang ceremony.

Over 50 mediums and 300 villagers gather during the ceremony to invite all the spirits from the Dong Phu Din forest to come and share wisdom, bless people and the lands, and enjoy musical performances put on by the villagers.

These ceremonies take place during April so villagers can ask the spirits to bless their farmland for good harvests, and again in October, to thank the spirits for their protection and generosity during the growing season.

For the people of Rasi Salai this ceremony is one of the biggest events of the year. Families from all over the province of Sisaket come to the ceremonies bearing offerings of whiskey, cigarettes, rice, incense, pig heads, flowers, betel nut, soda, fruit, and chickens.

Many of the villagers at the ceremony are elderly and feel a deep connection with Chao Pho since they were children. Chao Pho provides them with a sense of protection and security for their land and their health. And in return for Chao Pho’s protection, they help protect the forest and the land.

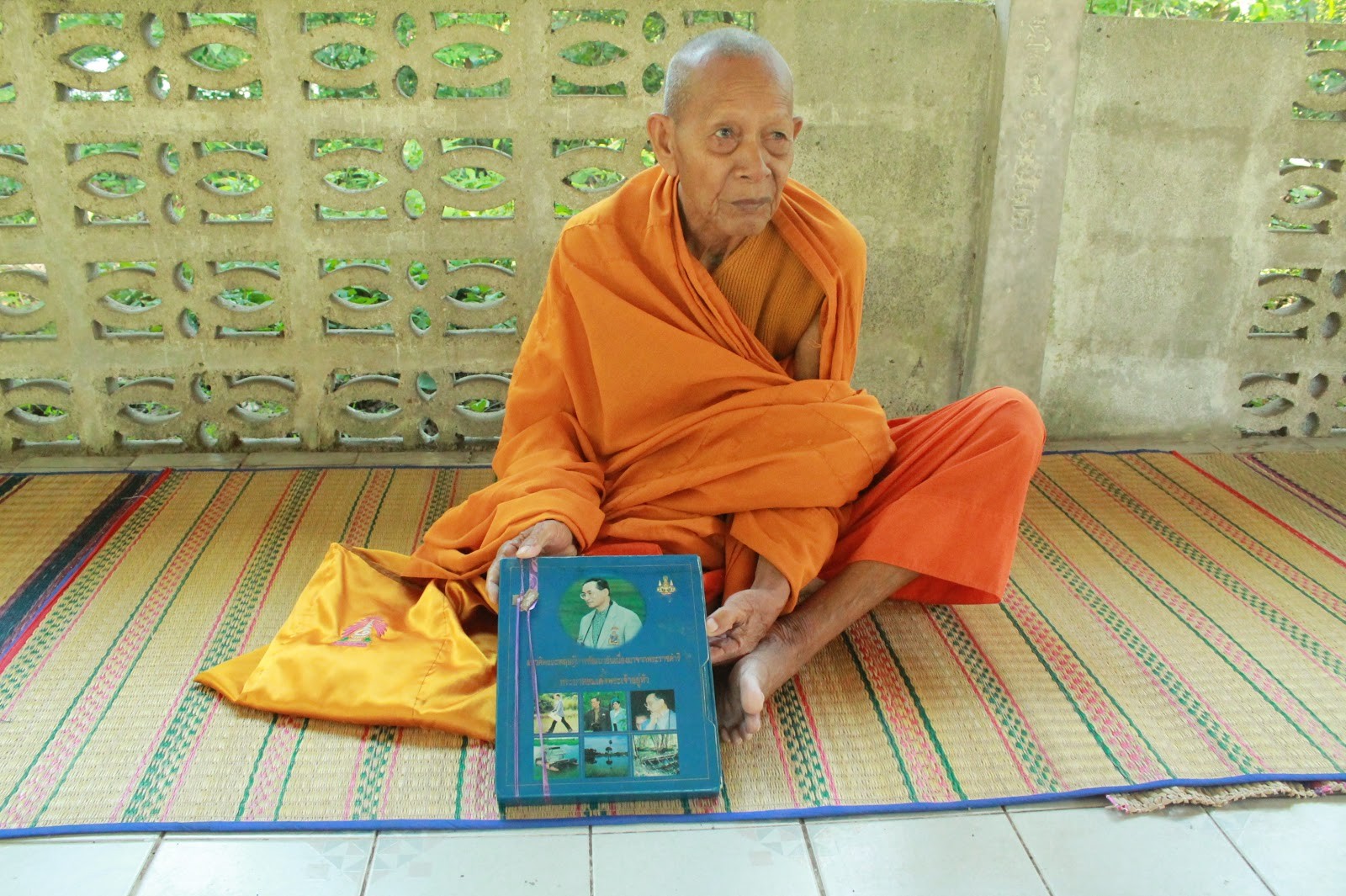

Amongst the many people at the buang suang ceremony is 86-year-old Sing Jumroen. Clothed in bright orange robes, he sits with his fellow monks watching the festival’s mediums and spirits dance and sing with villagers. Sing has been a guardian of the Dong Phu Din forest for the past 60 years.

“The government’s job is to take care of the people, the land, and the trees, but not to own it,” Sing says.

Sing’s determination to protect the forest is matched by the government’s desire to exploit the land for development.

Sing Jumroen sitting in the shrine at Don Phu Din. He has been the leader of several protests against government operations that threaten his home and neighbors livelihoods.

A sacred forest in crisis

Back in 1979, the Royal Forest Department (RFD) granted a concession to the Sisaket Forestry Logging Co., Ltd (SFL) to start logging operations in Dong Phu Din forest, the home of the Chao Pho spirits.

The SFL began cutting down trees in the Dong Phu Din forest and planting eucalyptus trees in their place, a with a high economic value, mainly for the paper pulp industry.

The RFD did not inform the local community about their plans to cut down the Dong Phu Din forest. The cultural and spiritual significance of the Dong Phu Din forest was unknown to the government at the time.

Because the RFD had full legal jurisdiction over the forest, logging operations were allowed to proceed without any consent from the villagers themselves.

The community was outraged. Word soon spread further afield, and people from all over the province came together to protest the logging operations to protect the home of the spirits held so dear.

Villagers sent multiple letters of complaint, one with over 7,000 signatures, to local and regional government offices, which were never responded to.

“The villagers do the right thing when it comes to respecting nature, but not the government. They only do things that make them look good. The villagers try to tell the government the reality, but the government won’t listen,” said spirit Pho Phra Ked concerning the government’s attitudes towards the environment.

With no response from the government, villagers took matters into their own hands and drove the concession workers off the land.

Villagers stopped selling food to workers, blockaded supply routes, and cut communication lines in attempts to make living conditions more challenging.

There was even gun violence during this time. Though shots were never fired to kill, villagers carried guns to defend against and intimidate the concession workers while the RFD and police sent armed personnel to protect the logging effort. “There was shooting every night,” recalls Panya Khumlarp, a community leader in Rasi Salai.

These were dark and desperate times for Rasi Salai. Many people were scared for their lives and their land. With the government ignoring their cries for change, it seemed that their protests were not making progress.

The villagers weren’t protesting alone, though. They had a little extra help from the spirits themselves.

Villagers and mediums of Rasi Salai held ceremonies to beseech the guardian spirits to help in any way that they could, and their calls were answered. During the operations several supernatural events occured, according to the villagers.

Medium Lamyong as the spirit Pho Phra Ked blesses offerings to the Chao Pho in the Don Pudin forest shrine on the day of the buang suang ceremony. Photo by Mike Eckel

One night one of the trucks used to cut down trees was said to have mysteriously turned itself on before driving itself into the river where it sank deep into the murky waters.

Another event occurred where a concession worker, without realizing it, drove his car into the river.

The villagers believe these events were acts of revenge and rage from the spirits of Chao Pho for the damage done to their home.

Fear and rumors spread among the concession workers. . They were afraid to work at night. They were at the same time afraid to fall asleep and never wake up again.

One night at the SFL base of operations, blood curdling screams rang out into the night: “I’m drowning! I’m drowning! I can’t breath!”

When people ran to investigate the source of the screams, they found concession workers squirming on the ground as if they were swimming. They believed they were drowning while on dry land. The workers were left with bruises on their chests and stomachs from struggling to swim to an imaginary shore.

People attributed the occurrence to the power of the spirits.

The combined forces of spirit intervention and the determination of villagers to protect their land was starting to make progress.

“The most important thing that really pushed the company out was the resistance from the villagers. They tried every way to make it so that workers couldn’t live in that area,” says Panya.

In 1981 villagers marched to the prime minister’s office in Bangkok to protest the logging operations. That year the government nullified the logging concession in the Dong Phu Din forest. The villagers of Dong Phu Din had won the battle for their forest.

The Dong Phu Din forest received the Thong Pitak Pa Phu Raksa Chiwit award from Queen Sirikit in 1996, an award dedicated to forest preservation.

The Dong Phu Din forest has since healed from the logging operations that happened 40 years ago. The trees that were cut down have since been replaced by lush growth.

But the forest is still not safe from the threats of industry.

The spread of offerings made to Chao Pho during the buang suang ceremony.

The forest with an uncertain future

More lately, Rasi Salai has been known for the controversial Rasi Salai dam which has flooded the wetlands just below the Dong Phu Din forest. But sand extraction operations have also had dire effects on the envirnment.

There have been river sand mining operations along the Mun River since 1992. Massive barges equipped with 12-meter-long pipes designed to gulp up sand from the bottom of the river continue to operate. Each boat can harvest up to 180 tons of sand a day.

The environmental damage that has resulted from the sand mining is extensive. The rate of river bank erosion has dramatically increased in the area, along with changes in river depth. The mining also destroys habitat for local species of fish, birds, plants, and animals.

These environmental changes severely affect villagers’ livelihoods for they can no longer harvest from the land the way they used to.

“When we suck the sand for ten minutes nearby trees on the river bank will fall down,” says Samret Jumroen, a former sand barge skipper. “That is the reason why all the trees, herbs, and natural resources on the river bank have been destroyed.”.

The area of the Dong Phu Din Forest has been lost due to these operations, along with massive flooding that has resulted from the construction of the local Rasi Salai Dam.

A sand barge in operation on the Mun River. The combined environmental damage from the dam and sand mining has resulted in around 93,000 rai of flooded land, according to the Wetland Association in Rasi Salai.

Villagers have been protesting against the dam and the sand mining company for years. Many social conflicts have arose because of these protests–conflicts between the government and the people, and conflicts between people within the communities of Rasi Salai.

Fights over government compensation has torn villagers apart. These conflicts had become so severe that neighbors stop talking to each other, marriages fall apart, and even physical fights break out amongst former friends.

But through all the stress and conflict, one thing brings the people of Rasi Salai together is the their faith in Chao Pho.

Twice a year, the buang suang ceremonies bring everyone together–even community members who have grown to hate each other. Everyone’s deeply shared faith in the Chao Pho helps them find a common ground to keep fighting for the land and the spirits that they love.

“This is how we fight with the companies–we use the Dong Phu Din spirits,” says Panya. But if deforestation and sand extraction continues, “the spirits will be gone.”

Cora Walsh is a environmental science student at Adolphus College in Minnesota. This semester she has been studying issues related to development, globalization, and human rights in Khon Kaen.