SPECIAL SERIES: SWEETNESS & POWER

The world eats a lot of sugar.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the world consumed 187,000,000,000 kilograms of sugar last year. The most visceral symbol of human-made largeness is Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza. The world ate the equivalent of 56 pyramids of sugar; India consumed nine of them, the European Union six, China five, the US three and a half, and Thailand almost two pyramid’s worth of sugar.

A few years ago, a group of scholars on the website The Conversation marveled at how sugar, this non-food food, is at the center of a global public health crisis and has at the same time yet become so dominant: it represents 20 percent of human caloric intake, it generated 9.4 percent of the agricultural monetary value worldwide in 2013, and it takes up a sizeable chunk of the world’s agricultural land.

They write, “It seems as though no other substance occupies so much of the world’s land, for so little benefit to humanity, as sugar.”

Boys Pilfering Molasses On The Quays, New Orleans, by George Henry Hall, 1853

Given sugar’s central role in modern life and the extensive sugarcane growing in the Northeast, The Isaan Record is putting out its most substantial series to date on this important topic, Sweetness & Power. We begin with three introductory research segments that provide a big-picture view of the historical rise and spread of sugar, its effects on the global environment, and then the effects of refined sugar on global diets.

We then bring you a series of features, articles, research, and opinion pieces that explore the relationship between sweetness and power and examine how “sugar” has influenced political and economic policy in Thailand and touched the lives of hundreds of thousands in Isaan who continue to grow sugarcane for sugar mills.

We take the name of our series from Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York, NY: Viking, 1985). Mintz argues that “Sugar…has been one of the massive demographic forces in world history.” It was because of sugar that “literally millions of enslaved Africans reached the New World,” and created a triangular trade that fed the industrial revolution and changed the eating habits of the world.

PART I: A world of sweetness

In 2018/19, world production of sugar stands at 179 million metric tons, enough to supply every human on earth with 23.7 kilograms of it for the year, or 15 and a half teaspoons of sugar a day. That extra teaspoon of sugar you just put in your coffee is, on average, just one of the 5,648 teaspoons of your annual sugar allotment.

The world has the equivalent of 43 trillion teaspoons of sugar to add to their coffee this year. Lucky for you, global consumption is slightly under production, so you had, on average, only 15 teaspoons of sugar, saving you the unnecessary extra calories of half a teaspoon.

The next time you add that extra teaspoon of sugar to your coffee, appreciate the revolution those white crystal grains have played in human history.

Those granules are not just a sweetener.

They have reworked the face of the earth, helped kicking off the massive forced migration of millions of Africans to the Americas, filled the coffers of governments (and made it a profitable item to smuggle), helped develop technical processes necessary for the industrial revolution, and jolted awake the laboring masses with it in the morning coffee and knocking them out at night with rum. Sugar is not just one of the world’s most profitable commodities today, it has largely redefined our relationship with food and our own bodies.

Total sugarcane produced worldwide, 1994-2017. Source: FAO

Sugar: a virtual food

What’s most remarkable about added sugar is that biologically it’s unnecessary for the human body. The body’s sugar needs can be met with the sugars found in fruit, vegetables, and other natural food sources.

Nonetheless, sugar has moved from a spice, to an ingredient, to a kind of food. Of sorts.

The phrases “empty calories” and “empty carbohydrates” were coined in the 1940s to describe foods of low nutrient density. They didn’t become popularized until the rapid rise of sugar in the human diet around 1970. In a 1971 book on food and health, the author rather understates the problem of eating too much sugar: “Our consumption of ‘empty’ carbohydrates seems to be a little too high, omitting valuable carbohydrate foods (such as vegetables and fruits).” The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) rather belatedly warned against empty calories in 2014, saying that favorite American foods such as cake, cookies, donuts, sods, cheese, pizza, and ice cream sometimes contain solely solid fats and added sugars that have little or no nutritional value at all. The USDA added, “A small amount of empty calories is okay, but most people eat far more than is healthy.”

These “empty calorie foods” are not “food” at all, at least in the sense that we understand the word, as they provide no nutrients, minerals, or vitamins. The more processed the sugar, the more empty it becomes nutritionally.

The bittersweet history of sugar in the modern world

Until just a few centuries ago, sweetness–the pleasant, sometimes intoxicating sensation in the mouth–had been an occasional treat in the form of fruit or honey.

Religious texts gave special status to honey–the miraculous work of bees that served ecosystems, humans, and bees. Buddhist and Islamic scripts both mention honey as a medicine. The Christian Bible has 62 references to honey, most often in the phrase referring to a future time of promise and good fortune in “a land flowing with milk and honey.”

Sugarcane might have been developed first in Papua New Guinea as early as 8,000 B.E. where it was fed to pigs. Indians were the first to develop a process to create a granulated sugar. Some 2,500 years ago when conquering part of present-day India, the Persian ruler remarked on encountering “the reed which gives honey without bees.”

Sugarcane was known but remained largely unremarked in the civilizations of the world up until 1000. However, as Mintz recounts, sugar held “the strange significance of a food that could be sculptured, written upon, admired, and read before it was eaten.” A Persian traveller in Egypt in 1040 reported that the sultan used 73,000 kilograms of sugar to fashion an “entire tree made of sugar.” A caliph in the fourteenth century had a mosque built purely of sugar for a celebration. At the festivities’ end, he invited beggars in to eat it.

The Western Crusades may have failed to “reclaim” the Holy Land, but they did bring sugarcane back where it was produced in small quantities for centuries in areas along the Mediterranean. Alfred Crosby’s Ecological Imperialism describes how the Portuguese lead in ship technology brought it into contact with sets of islands in the Atlantic like Madeira where sugarcane was introduced. An innovative water-driven mill, know-how from Sicilian advisors, and finance from Genoa increased production to about 69,000 kilograms of grain sugar in 1455. A fleet of 70 ships kept supplied the small but growing market in Antwerp. Still, the annual per capita amount of Madeiran sugar in Europe was only around one gram–a mere quarter spoonful.

There wasn’t much sugar to be had and what there was of it cost dearly.

An unskilled English laborer around 1400 made around £4 a year–about three pence a day for the laborer; four for a weave, and six for a skilled mason. It would take a laborer one day of work to buy a gallon of poor-quality wine and two days for a goose. If they wanted something sweet, it would take a third of a day to buy a pound of honey but it would take seven days’ of work to buy a pound of sugar; it would take 62 pounds of honey but only 3½ pounds of sugar to buy a cow. At the same time, two days of work could buy an esquire or constable in the army a pound of sugar while a sergeant-at-law could afford ten pounds of sugar a day, and a fairly well-to-do English earl could afford 55–if it was even available.

Sugar was perhaps better known at the time as a medicine in Europe. A sixteenth-century writer mentions its salubrious effects on health, but also that its use “makes the teeth blunt and makes them decay.” An ancient condition, diabetes, was tied to sweetness and coined as “Diabetes mellitus” (honey diabetes) in 1674 (although the author had tied the condition to increased consumption of sugar and not honey).

What eventually turned sugar from a rare spice and medicine to a commodity was the introduction of sugarcane to the Americas. In the tropical climate, sugarcane thrived. But indentured servants from Europe and indigenous people in the Caribbean died off too quickly from the brutally labor-intensive work. In 1518, the Spanish crown approved the transportation of slaves from Africa to work on America’s sugar plantations. By 1550, 3,000 sugar mills had been set up in the Americas. About 19 percent of the African slave trade to the Americas occurred during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

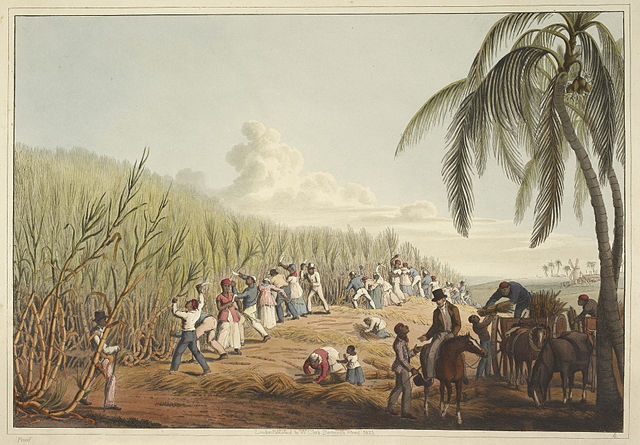

A sugarcane plantation on Antigua in 1823. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Even by 1700, the annual English per capita consumption of sugar was a mere 1.814 kilogram or a little over one teaspoon a day. Sweetness was counted in drops and grains; something to be taken in small measure, a precious spice, a rare condiment largely out of the reach by all but the best off. For common folk, happening upon a honeycomb was a rare but special treat.

Sugar, sucrose, came in the form of molasses, brown sugar, or white sugar, although the latter for centuries was awkwardly packaged as a “sugar loaf” that required an axe and special tools to chip away at it.

It was in the eighteenth century, though, that sugar was transformed from a symbol of power to real economic power. Newly developed steam engines increased the efficiency of sugar extraction. At the same time, more slaves were needed to move the cane to the mill. More than half of the African slave trade the New World took place in the eighteenth century, with nine out of ten slaves transported on ships under British, Portuguese, and French flags.

Mintz writes that as sugar became more plentiful, “its potency as a symbol of power declined while its potency as a source of profit gradually increased.” Now, “producing, shipping, refining, and taxing sugar became proportionately more effective sources of power for the powerful.”

As the tropical treats of coffee, tea, and cocoa made their way into England by the mid-seventeenth century, these intensely bitter products were sweetened by American sugar.

Sugar created two triangular trade patterns: industrial goods sold to Africa for slaves who came to the Americas to work on sugar plantations that sent sugar back to England to meet the growing popular demand for these sweet, energy-loaded empty calories that in turn hyped up factory workers to produce more goods. Another trade triangle brought sugar from the Caribbean to the American English colonies who made molasses into rum that was then exported, along with tobacco, back to the English Isles. These two triangular trade routes created huge profits for plantation owners, financiers, shippers, and industrialists, and provided the British government with ample opportunities to immense taxes at every transaction.

Sugar fueled the frenetic growth of England’s trade. Theo Barker in Megalopolis: The Giant City in History observes that “West Indian sugar became Liverpool’s main import” and the 18,850 tons of sugar that went through London’s port allowed the “exotic” sugar to find its way “to the provinces.”

The government benefited as well. Sugar taxes collected in 1781 were £326,000. By 1815, that amount had grown more than ninefold to £3,000,000.

With the flood of cheap sugar into England, honey fought, and finally lost, its centuries-old battle with sugar as the nation’s top sweetener. In 1250, sugar was about 50 times more expensive than honey. By 1800, honey was only 40 percent cheaper than sugar. And by 1850, honey was priced out when it was nearly four times more expensive than sugar.

Over the course of two centuries, per capita sugar consumption in England had increased by nearly 25 times–a little more than a teaspoon a day in 1700 to 5.32 teaspoons in 1800, to 26.6 teaspoons in 1900. To ease its consumption, the urbane sugar cube, individually wrapped, first made its appearance in Paris in 1908.

A sugarcane plantation in the Americas. Credit: Epic World History

Domination of sugar and its sweet benefits

Sugar quickly supplanted and underpriced honey as a sweetener. Americans consumed an average of 30 teaspoons of sugar a day compared to half a teaspoon of honey. World production of honey in 2017 was 1.86 million tons, which in today’s price of honey per kilogram would be valued at $6.53 billion. Sugar production was in 2017/18 was 194,496,000 tons and worth, if calculated in today’s price of white sugar, $55 billion. The international price for a kilogram of honey is $3.50–more than twelve times more expensive than sugar which goes for just $0.283 per kilogram.

According to the 2017 statistics of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, almost 60 percent of the earth’s agricultural land is dedicated to cereal crops, rice, and soybeans. About 2.6 percent are given over to fruits such as apples (0.44%), oranges and tangerines (0.54%), mangoes, mangosteens, and guava (0.39%), grapes (0.55%), and olives (0.67%). Another 2.02 percent is given over to nuts like peanuts.

Sugar (sucrose) primarily comes from sugarcane (84%) and sugar beets (16%). Sugarcane uses 1.71 percent, or 274,709 square kilometers, of the world’s cultivated land while sugar beets account for another 50,680 km2, totalling 325,389 km2 or 2.02 percent of agricultural land.

That might not seem like much, but it’s equal to sugar growing on every inch of the United Kingdom and Taiwan combined. It’s also equal to all the land dedicated to the world’s output of most of the world’s key vegetables: broccoli, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, cucumbers, eggplant, leeks, lettuce, onions, shallots, spinach, string and green beans, and tomatoes, as well as all the world’s main commercial berries (blueberries, cranberries, gooseberries, raspberries, and strawberries).

According to the World Wildlife Fund, sugarcane in 2015 used at least a quarter of all farmland in a dozen countries. Governments and sugar companies are drawing up plans for greatly expanding the area under sugarcane cultivation.

There’s clearly someone making a lot of money to feed our craving for sugar.

Outside of cereals and rice, sugarcane is the globe’s third most valuable agricultural product. Sugarcane has the largest biomass of any agricultural crop.

There are no easily available statistics showing how many sugarcane growers there are in the world. An Indian government website states that sugarcane “provides employment to over a million people directly or indirectly” in the country as well as “contributing significantly to the national exchequer.” Cane sugar makes up 70 percent of the value of exports from Cuba.

One piece of research indicates that in 2008 the sugarcane sector in Brazil directly created $28 billion, or about 2 percent of Brazil’s Gross Domestic Product. But when “taking into account total sales of the various links comprising the sugarcane agri-industrial production system,” the total value is actually as much as $87 billion. These links in the system generated $478 million in sales of herbicides and pesticides and $2.3 million in fertilizers.

Outside of the governments and companies benefitting from sugarcane production, there are millions of small-scale farmers throughout the world feeding the mills.

Just seven countries (the EU considered as one country) produced more than two-thirds of the world’s sugar in 2018/19. None of the historical sugar powerhouses of the Caribbean are in the list except Cuba which came in at 19th place with less than 1 percent of global production.

The five largest producers were also the largest consumers of sugar, comprising about 48 percent of all sugar consumed. Just four countries dominate more than two-thirds of the world’s sugar export.

Of all the sugar produced worldwide in 2018, 31.5 percent was exported, and 28.5 percent was imported. Eight countries import 44.6 percent of that: Indonesia (9.5%), Algeria (4.7%), United Arab Emirates (4.3%), Malaysia (4.1%), and South Korea (3.9%), as well as two of the largest consumers: China (8.4%) and the US (5.1%).

In this Part I of our series on Sweetness & Power, The Isaan Record has looked at the rise of sugar in modern society, one that tied together the human predilection for sweetness with enslavement, colonialism, huge profits, substantial government revenues, and the continued expansion of this tropical grass over the globe.

In Part II of this series, we examine the impact sugarcane cultivation of this spice-turned-food has had on the environment.

Additional material by Teresa Montanero who majors in Anthropology at Georgetown University and Charlie Wall who majors in history at Amherst College. Both studied about development and human rights issues in the Northeast in spring 2019.