By Panupong Thongsri

Molam is one of the most important performing arts of Northeast Thailand where it not only functions as a type of entertainment but also upholds local culture, including popular folktales and literary works. Often molam performances creatively tell stories that express ideas about social change and development.

In this article, I would like to take you on a journey to learn about the development of molam in various eras before the genre became a staple of entertainment culture in the Northeast.

Before digging into the history of molam, I would like to consider the question of why people in the region’s premodern past would gather and congregate in one place.

As the well-known Thai historian Sujit Wongthet writes, people in the past would usually gather when there was a special event in the community like rituals and ceremonies.

“All people were involved in rituals after death (because bronze tools found in their graves),” Sujit writes in an online article from 2018. “There were activities like playing games, dancing, playing the khaen and singing lam to call for and the sending off of the spirits (of the dead) to the world after death (in the latter days known as Ngan Huean Di, or a game of joy in the house of the dead).”.

[Note: The khaen is a mouth organ of the Lao people made of a set of six to eighteen long bamboo pipes each with a tiny metal free reed.”]

Based on archeological evidence of the bronze drums of the Dong Son culture found in Southeast Asia, dating back about 2,000 to 3,000 years, I would like to argue that the images on the drums show lam singing traditions that were part of agricultural rituals to ask for rain. These might be rituals similar to the present-day Isaan tradition of Soeng Bang Fai, a dance associated with the Bun Bang Fai, or known in English as “the rocket festival,” held to celebrate and encourage the coming of the rains.

Images found on Dong Son drums (left) and a procession of the Soeng Bang Fai ceremony in Roi Et’s Selaphum district (right). Photos from Matichon Online and November25.

Here is an example of a song lyric that accompanies the Soeng Bang Fai. It follows the tempo of khaen playing but without really following the specific meter and rhyme schemes of the kap, one of the common Isaan literary styles:

บั้งไฟบูชา พระยาแถนเจ้า bang fai bucha phraya thaen chao

ฝนอั่งเอ้า ตกหล่นลงมา fon ang ao ok lon long ma

พันธุ์พฤกษา พืชผักต่าง ๆ phan phrueksa phuet phak tang tang

แสนดูทาง เฮ็ดอยู่เฮ็ดกิน saen du thang hed yu het kin

(The rockets to worship the Phaya Thaen god

to make the rain come pouring down

Trees and plants of all kinds

Growing to feed our people)

The style of this kap is rather simple. It uses few words that will be sung to the sound of khaen playing in a ritual asking for rain before the start of the farming season.

The form of the kap was later developed into khlong san, another common Isaan literary style, with tonal characteristics to make the language sound more elegant.

The verse form khlongsan does not clearly specify the number of words but each line should not have more than nine words. The content of khlong san is often linked to literary works dealing with worldly and religious topics.

Every local version of the lyrics for the Soeng Bang Fai songs mentions popular folktales like Pha Daeng-Nang Ai that refers to the rocket festival tradition as a competition to ask for rain for rice farming. Another mention to this tradition is the wearing of a kawom, or a cloth hat, which is still common today.

The evolution of Isaan’s literary forms of the kap, khlong san, and klon is linked to important local traditions which were often used in rituals and ceremonies addressed to spirits and gods like the Phaya Thaen, the god of rain.

As Isaan society developed, these literary forms accompanied by music, for example molam, came to play an important role in community’s public meetings and events.

In Isaan, molam was traditionally performed while seated with a small audience surrounding the singer. It’s referred to as molam nang (sitting molam) or lam phuen (singing on the ground). Through the latter half of the 20th century, the introduction of stages and sound systems–standing performances in front of a larger audience–became more common.

Storytelling in the form of khlong san has been common in the Northeast for centuries. Its verses are short and often deal with stories about courtship and romance. Evidence of this form can still be found in the local variations of lam khon sawan, lam mahachai and lam si phan don. However, I would not dare to declare whether this form can already be called molam or not.

In the 16th century, under Lao rulers like Photisarath, scholars and intellectuals composed various literary works about both worldly and religious matters. These includes the works of Phra Ariyawongsa, Phra Samutkhot, Phra Maha Sangha Pasaman and Phra Thep Mongkol. They wrote in the styles of khlong san and hai, which are collectively referred to as lam. Some examples are lam phra kaew, lam mahachat and lam phra bang. Sometimes the word phuen [ground or floor] was used to describe these styles like in various phuen styles like phra saek kham and those that developed in Ubon Ratchathani and Vientiane.

This might be the origin of the term molam. The first word, mo (mɔ̌ɔ), is considered to be an original Tai word which might be pronounced with different tones. It appears to be a word from the Tai-Kadai language family, meaning the one who knows or is an expert.

As for the word lam, I believe it comes from the word, lam nam, which means a set of klon verses used to sing with rhymes to make it rhythmic. It is notable that lam nam and lam nám, meaning “river,” is spelled with different tone marks. If the tone marks are removed, they become the same word.

So how is that important? I want to point out that normally, Thai people often naturally shorten a multisyllable word into two syllables. The word mo lam nam (mɔ̌ɔ lam nam), which means an expert in singing a long composed story, is shortened to molam (mɔ̌ɔ lam). [The author assumes that] the word lam nam was cut and added to word klon as klon lam instead, meaning a composed story with rhymes and used for singing or lam.

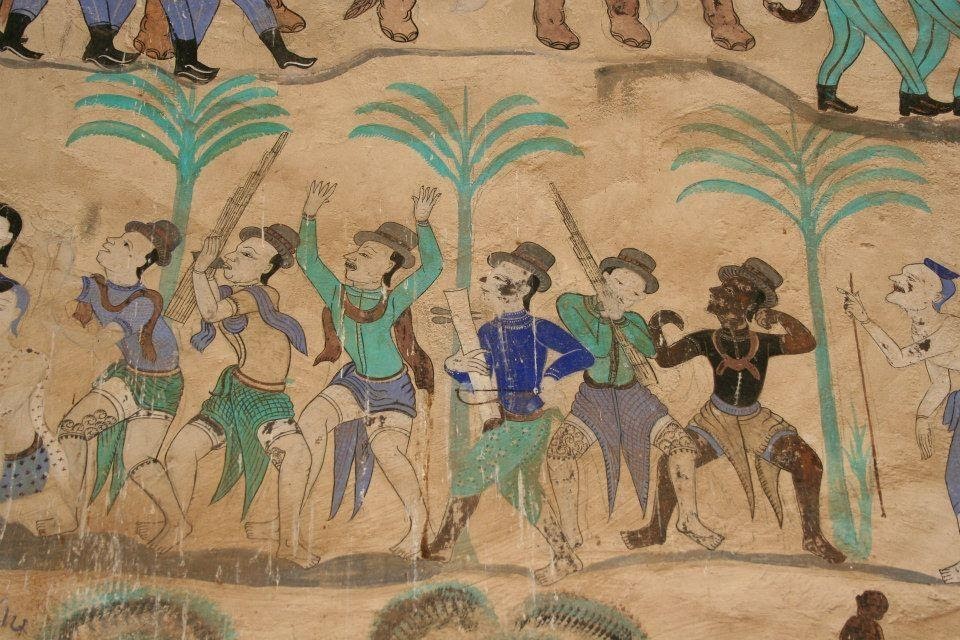

Mural from the Lelai Forest Temple in Na Dun district of Maha Sarakham Province. Photo by Lankum designTemple murals, known as hup taem in Lao, show how Isaan people in the past celebrated with molam performances.

Molam Chomsri Banlusin and Molam Khun Thawonphong, the first-ever recorded Isaan molam artists. (Screenshot from a Youtube video posted by Tong Anurak)

People later found that just singing klon verses was not very entertaining, so they added the khaen as a musical instrument to provide accompanying music.

In the past, there were not many types of khaen available to adjust for molam singing, and each molam performer would sing in a different key.

Based on the evidence I found, this issue was solved by what is called “melody reading.” The molam singer sets the key in the introduction with an O sound and the khaen player adjusts the melody accordingly.

Later when musical scores became common, the words “O-no…” or “O-la-no…” were used in the introduction of the verse of the khlong san form. However, this is less common in lyrics written in the hai form. These introductory words give the khaen player time to adjust the key and follow the molam singer.

Listen to audio examples of the “O-no…” and “O-la-no…” introduction:

The length of the “O” varies as the molam singer usually performs both short and long vocals. Long vocals are usually sung in a slow and long-drawn way (example 1) while short vocals are sung in a fast and rhythmic manner (example 2).

The khaen player follows the molam singer and has the following six modes available:

Yao [long]: yai, noi, and se (sound examples in the links)

San: sutsanaen, po sai and soi (played with a khaen modified with khi sut, a wax-like substance from the nest of stingless bees)

Listening to the songs of Molam Chomsri Banlusin and Molam Khun Thawonphong, the first ever recorded Isaan molam songs from 1940, it appears the introduction of the lam singing was the same as today, but the rhythm and the scale of these early khaen were not even in tune. Later, the characteristics of khaen modes and klon lam were adjusted to be in the same rhythm of a slow melody so that the rhythm of the khaen was the same as the singing.

The molam troupe of Khum Lao performing at a temple in Maha Sarakham Province, 1964. Image from the website of the Isan Arts and Cultural Club, Chulalongkorn University.

As molam lyrics dealt with both worldly and religious matters, molam performers were usually seen as knowledgeable and wise. Of course, they had to have a good memory and the ability to read, which distinguished them from most ordinary folks in the past. The most highly regarded were those who mastered the art of klon verse and melody composing. It was considered the highest skill of literary expression of the Isaan people.

I am ending this article in the hope that it will stimulate the readers to criticize and exchange ideas and knowledge about the evolution of molam so that the genre can withstand the risk of being lost and continue to flourish.

Note: The views expressed on The Isaan Record website are the views of the authors. They do not represent the views of the organization, its editorial team or any of its partner organizations.