In July, the share of new Covid-19 cases in Thailand shifted decisively from Bangkok to the rest of the country. By early August, Bangkok comprised only a fourth of cases, but government vaccination efforts still centered on the capital. At a time when there’s a shortage of vaccines, why hasn’t the distribution of vaccines been more equitable regionally?

By The Isaan Record

The good news is that Thailand has seen a 173% increase in the number of vaccines given in just one month, from July 9 to August 8. Impressively, of the 50 million making up the target groups–medical staff, public health volunteers, front line officials, people in general, and the elderly and those with existing conditions–the number of doses rose by 305%. Also it is notable the two latter, most deserving target groups increased by 391%.

All well and good.

The bad news is that the vaccination rollout remains distressingly skewed. Yes, the number of doses given to the elderly and those with preexisting conditions has increased nearly fourfold. That dramatic increase is simply because so few in these two groups had received a vaccine shot earlier. These two groups, representing 18 million people and 36% of target groups, had received proportionally only 13 % and 8 % of doses, respectively. The percentage who had received a dose rose very modestly, to 17 and 10%.

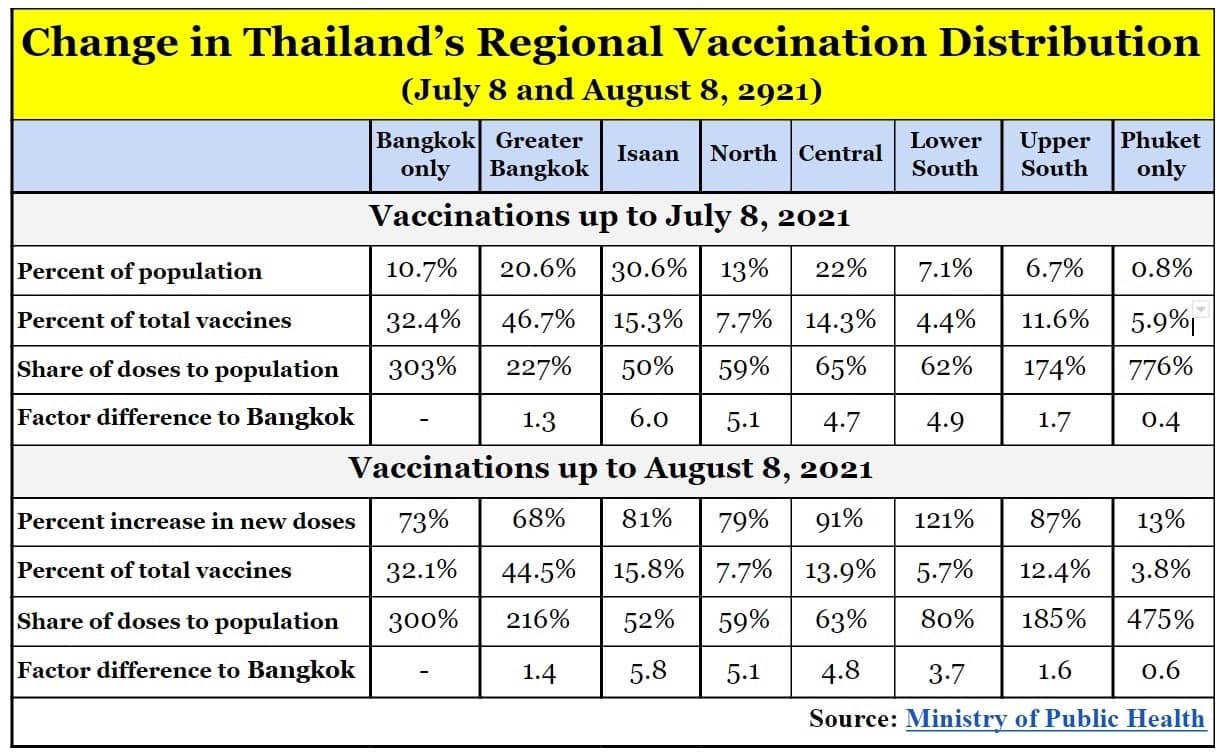

We reported last month that there was a sharp gap between vaccination rates between Greater Bangkok and most of the rest of the country. Calculations made from the statistics in the Ministry of Public Health’s update on vaccinations shows that Greater Bangkok consumed 48% of first doses of the vaccine, 235% higher than its share in proportion to population. All the other provinces combined received just 65% of their “fair share.” The upper South received 154% of its share. Phuket got even more first doses than Bangkok per population; it got 12 times more than Isaan of first doses and 21 times more second doses.

The rest of the regions got notably less: the Central region got 63% of its share per population, the lower South got 65, the North, 58 and expectedly, Isaan got 48%. Did these numbers change?

Pursuing a “Bangkok-first” approach to vaccinations

Faced with few cases and enthralled by thoughts of creating Covid-free tourist havens, the government confidently rejected joining the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access (Covax) effort in February.

The government was caught flat-footed when hit by the third wave. It had put all its hopes in the weak vaccine, Sinovac, and an underperforming locally produced AstraZeneca vaccine. Desperate, health officials rushed to put in orders for vaccines only to find Thailand at the end of the line.

Five full months after refusing to join Covax but without any prospects of getting vaccines any time soon, the government in July humbly joined.

Facing a dearth of vaccination doses, one might think the government would reconsider its approach.

While Bangkok (and the greater metropolitan area) could perhaps make the argument earlier on that it should use the lion’s share of the vaccinations as it had more than half the cases, in June the trend was clear as outbreaks struck in every corner of the country.

Had the Thai government recognized the alarming imbalance and taken measures to address it?

Apparently not.

As the government congratulated itself on reaching 20 million administered doses of the vaccine on Aug. 8, the update by the Ministry of Public Health shows that the government continued to privilege Greater Bangkok and certain groups of people, above those who deserved and needed the vaccine more (or at least equally as much).

Regional Disparities

From the start, vaccines have been unequally distributed. Up to July 8, Greater Bangkok took 47% of all doses while representing only 20.6% of the population (see the table below). In proportion to population, it received/gave itself 227% of vaccine doses while Isaan received only 52 % of its share.

If, say, 100 doses were distributed equally throughout the country, Isaan would get 30.6, Greater Bangkok, 21, and Phuket less than one dose. Up to July 8, though, Greater Bangkok got 46, Isaan 16, and Phuket three and a half doses. Doses provided to Isaan vs. Bangkok, in proportion to population, the factor of difference was 5.8. It is as if for every six doses Bangkok took for itself, it gave one to Isaan.

Despite the scarcity of vaccinations, the medical establishment determined it should have a third dose, given the track record of Sinovax (which Thailand phased out in late July) . Low on vaccines and cases rising outside of Greater Bangkok did not, however, seem to alter the government’s distribution of doses. Between July 9 and August 8, the percentage of total doses that Greater Bangkok took for itself in proportion to population dropped a bit to 216%, meaning vaccines were shared more in the country.

Countrywide, there was a 75% increase in overall number of doses. Isaan’s share of new doses was 80% while the Central region’s share went down to 70%. The biggest change was for the lower South whose share of new doses rose considerably to 129%. Phuket’s share increased modestly, as it already had received five times more than its share according to population. In conclusion, the increase in vaccines throughout the country merely mirrored the inequality in the unequal distribution prior to June 8.

Priority Groups gone awry?

Every country in laying out vaccination plans prioritizes who first gets the shots. As certain groups are more vulnerable to the Covid-19 virus, countries have all made sure the health providers are first made safe so they can take care of the rest of society through the crisis. Then typically come those with preexisting conditions and the elderly.

Thailand was no different. Reuters’ “Vaccination Tracker” says that the Thai government offers vaccinations according to “occupation, medical condition and age” and lists the two priority groups:

PRIORITY GROUP 1

✅ Front line medical staff (health workers)

✅ With medical condition (people with chronic diseases)

✅ At least 60 years old

✅ Front line medical staff (disease control workers in contact with patients

PRIORITY GROUP 2

✅ Non-front line medical staff (other medical and health personnel)

✅ Tourism sector workers (tourism-related workers)

✅ Air transport workers (air travel staff)

✅ People who travel cross border (international travellers)

✅ General population (the general public)

✅ Diplomats

✅ Staff of international organisations

✅ Foreign business people and expatriates

✅ Service sector staff (workers in the industrial and service sectors)

How well has Thailand kept these priorities in mind? Medical staff, estimated to make up 712,000, exclusively took all the third doses and so this group has received 248% of its doses (“200%” indicates two doses on a two-dose vaccine). This group is the only one completely vaccinated, if not overly so. Thailand designated the one million public health volunteers as “disease control workers in contact with patients.” Its members have received about 17% of the doses needed to be fully vaccinated which would require 1.25 million more doses.

As for the most vulnerable, people with chronic diseases and the elderly represent more than a third of the government’s target of 50 million, but they’ve received the least amount of attention. These two critical groups have received only 16% of the doses necessary to be fully vaccinated.

One reason that the most vulnerable in Thailand are not getting vaccinated is because other groups have taken their place. Thailand has designated 1.9 million “frontline officials” as apparently more important. This group has gotten about 39% of the doses necessary to be fully vaccinated. Anecdotally, there are officials in the Northeast who have gotten vaccinations and have no particular “frontline” function. But the number is relatively small.

A larger group are those who have received vaccinations for touristic purposes at “Sandbox” locations, like Phuket that received 760,000 doses, equivalent to 72% of the residents being fully vaccinated.

But by far the largest group is the “general population.” This group has received 39% of all vaccines, and nearly twice as many as the elderly and those with chronic conditions.

From a distance, it seems like the government never made an honest attempt to get vaccines to the most vulnerable, except, perhaps, in Bangkok. In proportion to population, the elderly in Bangkok received five times more doses than the elderly in Isaan and almost six times more than the olderly in the Central region. And those with chronic conditions were much more fortunate in Bangkok as they were almost seven more times more likely to be vaccinated.

Public health volunteers, on the other hand, were much more favored outside of Bangkok (where they are presumably less common).

But the largest group shows the largest gap. For every ten members of the general public in Bangkok who got a dose, only one in the North did.

The statistics for Bangkok vaccinations undoubtedly include a lot of people from elsewhere who went there for a shot.

People in the provinces encounter crashing hospital websites. New allotments of vaccinations are announced by provincial officials; online registration fill up and close within minutes. Through connections or a lucky shot on an online registration, people from other regions make the trip to Bangkok to get a vaccination. Some may be the vulnerable but many are members of the general public who are desperate to get a vaccine while they have a chance.

Equalizing Vaccinations

There are signs that a more equal distribution of vaccines is emerging. It may be good that Bangkok has neared its saturation level. It may allow for a more determined effort to get vaccines out to other regions. Thailand also has a first-rate registration system that makes it difficult for people to seek a better second dose.

The Covid-19 crisis has brought about the best and the worst in nations. The course of the virus has varied from society to society. Canada initially took a very egalitarian approach by giving out single doses and hoping that new doses would be forthcoming. Aflush in vaccines, as many as a million Americans have sneaked a third dose. Then, last week and on questionable scientific grounds, the United States decided to give a “preemptive” third dose to not just the elderly and those with conditions, but to everybody. For every “over-dose” an American gets, there is one less dose for someone in a country with greater need.

The Thai government has bungled its response to the crisis. There is some hesitancy among the population, not so much against vaccines as against the government. Many already distrusted the government for its inefficiency and using Covid-19 as an excuse for cracking down on critics. Giving a third dose to medical personnel communicated that the vaccines weren’t effective. Common people came to understand, wrongly or rightly, that they’re being goaded to get a vaccine of questionable quality.

To date, the Thai government has not distributed vaccinations fairly or equally. It is not a surprise as Thailand was judged as the most unequal country in Southeast Asia. Where hierarchy and connections are celebrated and notions of equality are frowned upon, common people, especially those far from the center, are usually overlooked.

It’s not too late, though, for the government to change course. The government can return its original plan and once again prioritize “people with chronic diseases” and those “at least 60 years old” – but this time, in the entire country. It can focus for the time being just on vaccinating these two groups. Afterwards, the government can systematically bring in other groups.

It’s not that complicated and it will save countless lives.

Relevant articles