By Paul Bierman

It is impossible not to stick out as a white foreigner living in Thailand.

I remember one time when I went to go eat somtam with a couple of teachers from my school in Chiang Rai and as we walked into the restaurant, an older woman shouted with glee, “Farang! Farang! Farang!” I have wondered if there could be a future for me where reminders like this of my foreignness won’t occur. And in thinking about that future, I turned toward Thai media and came across some cases of not actually foreigners, but Western-looking half-Thais (luk krung na farang) that helped me think about what “not looking Thai in Thailand” means. These half-Thais stick out, and it seems to me they are only accepted as Thai people if they can out-Thai the other Thais. If not, they might as well be seen as a total foreigner, like me.

In the 2015 children’s book, Jack and Jim by Piyapongse Mokapon, the luk krung protagonist Jim is orphaned when his English father and Thai mother die in a car accident. Jim soon leaves Bangkok to live in rural Khon Kaen with his Aunt Nii, who warns Jim to stay out of the way of her child-disliking husband Muan.

After six months, Jim has finally gotten used to eating Isaan food after subsisting on boiled eggs that Aunt Nii prepares especially for him. Jim still hasn’t gotten used to his new home on other fronts though. The closest thing Jim has to friends in his class are two bullies, Gai and Pet (Chicken and Duck), who call him names every day.

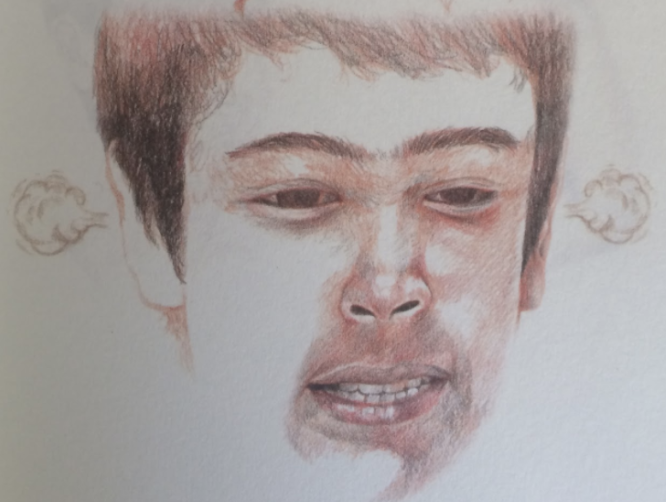

The pictures of Jim in Jack and Jim by author and illustrator Piyapongse Mokapon seem to be at odds with the Jim described in the book, who bullies call “red-head.”

One day, a friend of Uncle Muan’s comes looking to sell an orphaned buffalo. Jim sees himself in the orphaned water buffalo, and on the verge of tears asks Uncle Muan to buy the buffalo for him. Jim names his buffalo Jack, saying “I should have a friend who is a farang, just like me.” On nights when Jim misses his parents, he sleeps in Jack’s pen, crying and telling Jack about his feelings. Jack eventually reveals to Jim that he is a talking buffalo, who has understood everything Jim told him. Oddly enough, Jack seems to be the only one concerned with how Jim is doing. The teachers at school never do anything about Jim getting bullied, and aside from buying Jack and making Jim hard boiled eggs, his new guardians aren’t doing much to help either.

Uncle Muan gives Jim some land to grow rice, but provides no guidance on how to do it. Jack tells Jim not to worry about it because farming is in his buffalo blood. After muddling their way through plowing the field, Jim starts to plant the rice. He hears laughter from behind him, and turns to find Gai and Pet making fun of him for not knowing how to plant rice. They offer to teach Jim how to plant rice, but only if he agrees to address them as “Teacher Gai” and “Teacher Pet.” Jim accepts their help and they help him plant. After, Jim tells us that Gai and Pet are not as bad as they might seem.

Jim getting annoyed with Uncle Muan, and the only illustration of Aunt Nii in the book

Jim still doesn’t quite fit in however, not until it comes time for the bang fai festival, which Jim learns is a traditional festival when villagers shoot rockets into the sky to remind the deity Indra to send down rain for the crops. Jim, Pet and Gai go into the forest to make gunpowder for their own rockets. Jim makes a batch of gunpowder that performs better than Gai’s or Pet’s because he adds sulfur to his mixture, which he learned about from his childhood in Bangkok, when he played with rockets and teachers told him that he would grow up to be an inventor one day. Gai and Pet are duly impressed, and let Jim prepare the group’s gunpowder for their rocket. The group has a successful showing at the village bang fai festival, though they don’t win. Only after Jim shows that he can make a better rocket and out-Isaan (or out-native) them do Gai and Pet finally start calling Jim by his name and not “farang” or “farang-Jim.”

Now that Jim has human friends, the story quickly skips to harvest time, where Jim cries tears of joy at seeing everyone in the community who comes to help harvest his rice. Jim tells us the lesson that he learned, that “Everyone has loved me and had hopes for me throughout. I myself was caught up in my own thoughts and feelings of being slighted. It made me see other people always from a bad perspective.” [this author’s translation]

The story ends happily for Jim, and in an afterword we find out that he eventually marries one of his classmates and they have many children together. But one thing still bugs me: I am not convinced that Jim was wrong to be upset with the people around him. Pet and Gai finally become his friends, but only after bullying him for six months. Aside from purchasing Jack, Uncle Muan seems indifferent to Jim and Jim’s struggles. Maybe Uncle Muan is intended to be a gruff Isaan farmer with a heart of gold, who should get credit for treating Jim like any other Isaan boy who has to learn life’s hard lessons on his own. But Jim is different from all his peers. If the adults in his life aren’t going to work on Jim’s behalf to get other people to treat Jim better, the least they could do is truly help Jim learn how to fit in. Instead, what actually happens in the book is by their inaction they teach Jim that he needs to make himself fit in, and then thank them for the opportunity to do so.

It’s hard for me not to see the book as a case of a Thai author excusing Thai people for their discriminatory treatment of luk krung.

But what if we look at the treatment of an actual half-Thai person? One without a talking buffalo for a friend. This summer saw the first season of MasterChef Thailand, a television cooking show. On the show there is one luk krung na farang contestant, Lisa Dawson. In episode 7, the contestants are make traditional Thai food, prepared and presented in a modern style. One of the judges, Chef Ian (Pongtawat Chalermkittichai, international restaurateur and Thai Iron Chef) yelled out at all of the contestants, “Your dishes today have to demonstrate to us that you’re a real Thai person!” While making rounds in the kitchen, he stopped to talk with Lisa, and picked up a bottle of pla ra (fermented fish sauce) sitting on her station:

MasterChef Thailand runner-up Lisa, cooking rice during the final episode while Chef Ian looks around the kitchen.

Ian: “Using pla ra?”

Lisa: “Yes, I’m Thai.”

Ian: “You can use pla ra?”

Lisa: “Yes.”

Ian: “You can use it?”

Lisa: “Yes, my grandmother is Isaan.”

Ian: “It’s strange. [Your competitor] Oak is Thai and can’t make Thai food, but…”

Lisa: “He’s the one going home.”

Ian: “You’re this competitive?”

Lisa: “Yes.”

Ian: “But you’re familiar with pla ra and you know how to use it?”

Lisa: “Yes.”

Ian: “That’s great. Good luck.”

Lisa: “Thank you.”

This is how remarkable it was to Chef Ian that Lisa, who grew up primarily in Thailand, would know how to use pla ra.

During Lisa’s evaluation the judges go out of their way to point out that they were impressed by Lisa’s Thai cooking skills in spite her being half-Thai. Judge Ink (M.L. Pasan Sawasdiwat, food critic) says to Lisa, “My eyes are closed [as I eat this], and I know that a true Thai person made it. This has real Thai flavor…You have the knowledge of being Thai.” Chef Ian himself overcomes his initial incredulity, saying to Lisa, “You can make food that is traditional, that is Thai, even though you yourself are luk krung.”

Though Lisa is experienced at making Thai food, many other fully Thai contestants such as Oak are not. Oak’s final dish included an overly-sweet sauce based on green curry. Green curry itself is categorized as palace food, not even the traditional food the contestants are asked to make. His failure causes Chef Pom (M.L. Kwantip Devakula, a restaurateur) to call his Thainess into question:

Pom: Oak, I’m looking for the green curry, and I can’t find it. Oak, what nationality are you?

Oak: I’m Thai.

Pom: And that is how little you understand about making green curry?

The other contestants who produce food that is too sweet or has no connection to traditional Thai food are similarly accused by the judges of being ignorant young people lacking in Thainess and too easily seduced by Western (farang) food. This is in direct contrast to Lisa, who demonstrates her Thai identity through Thai cooking, and not only appreciating Western food. But this appreciation of Lisa’s Thai cooking ability continues to be tied up with the idea it is surprising a half-Thai person can cook Thai food. On the season finale, where Lisa comes in second place overall in the competition, she is introduced as “[the] half-Thai woman with a Western face and a Thai heart” (sao luk krung na farang hua jai thai).

For both Jim and Lisa, fitting in comes at a price. For Jim, it is internalizing that it is normal for him to be treated as an outsider. For Lisa, it is being tokenized as a shining example of a luk krung who embraces her roots. But neither are allowed to just be people without their heritage coming into play.

As for me, the cost of hearing “Paul, you’re just like a Thai person” for doing something like eating somtam or knowing how to wai properly, is the reminder of just how far I am from fitting in.