When Siamese soldiers crushed the Holy Man Rebellion and scoured the area for escaped rebels, terrified locals sought refuge in temples while others turned to local spirits for protection. A local chief who became an executioner of rebels bore a ring of black which returned to black even when scratched. Had the ring absorbed the malice of its bearer and the dark crimes he committed? Was he the “Sauron of Isaan”? Guest contributor Janista Aphasaengphet investigates, with photos by The Isaan Record intern, Tatiya Trachu.

Story by Janista Aphasaengphet

Photos by Tatiya Trachu

Besides official records in historical books, oral accounts preserve the memory of Isaan’s deadly struggle between the Holy Man Rebellion and the government that broke out in Ubon Ratchathani in 1901-1902. Ban Saphue’s current residents recount stories passed on from their parents and grandparents who lived through the period when citizens took up arms against the government in their hometown.

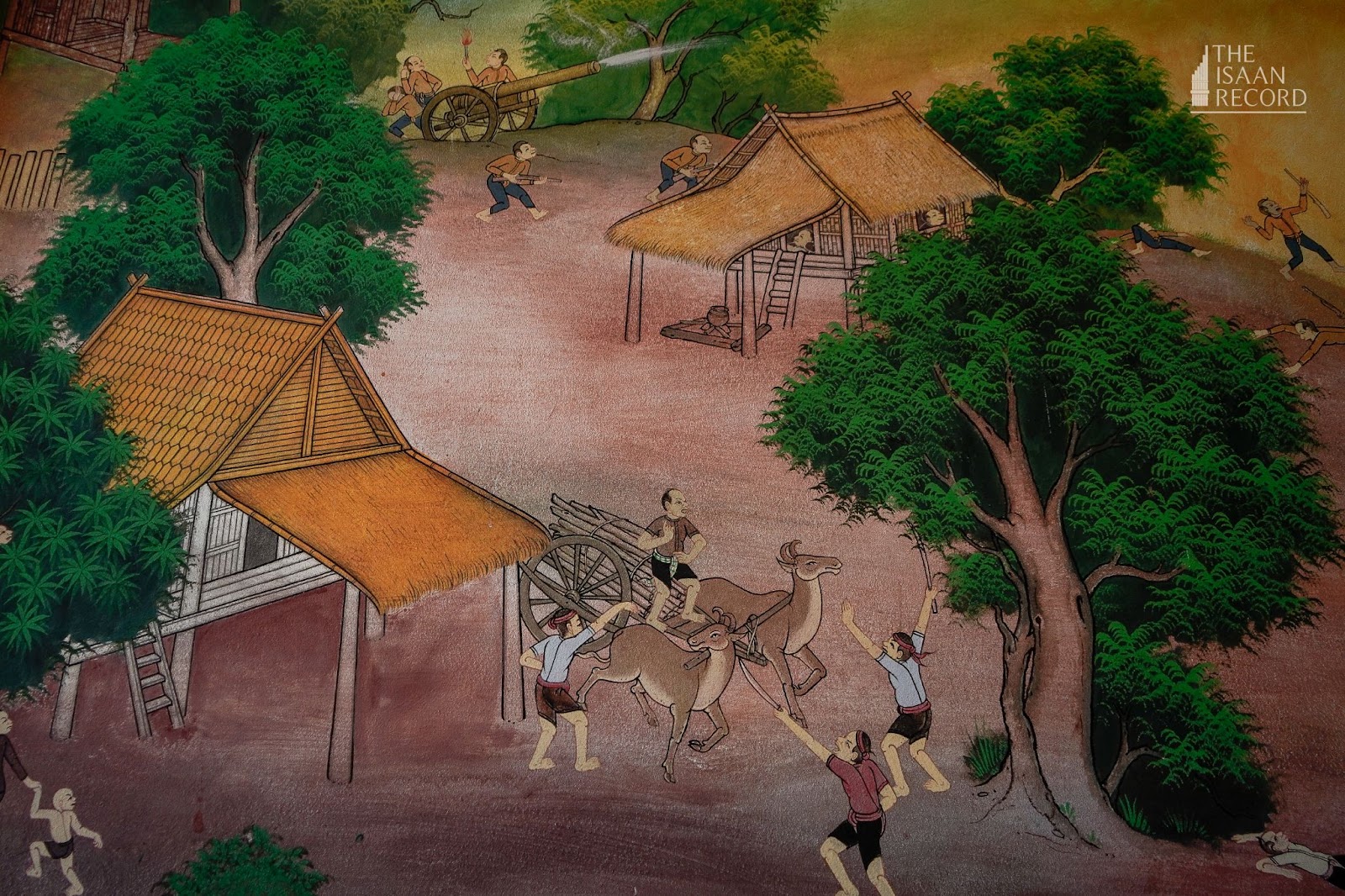

The Battle of Non Pho: ordinary life and shelter

“I’ve heard that there are a lot of bodies buried around Non Pho, where the battleground was. For battles in the old times, there were no guns, only ngao [halberds] or a type of weapon used to decapitate people. They dug holes to bury the bodies and dumped them down there,” says Nikhom Promsrimai, a local resident of Ban Saphue in Ubon Ratchathani province, on the subject of the Battle of Non Pho where hundreds who rebelled against the government had died.

“I only know that they hacked at each other, hitting wherever they could,” he says. “Anyone who died was thrown into the [mass] grave.”

There are also stories of what those who did not take part in the battle did at the time. Beyond the violent fight, the sound of cannon fire, and men killing each other with halberds, 72-year-old former teacher Phinit Prachumrak recalls what his grandparents told him about the atmosphere in the village during the conflict.

In April 1902, villagers who did not take part in the fight had to seek shelter in temples or chapels. They hid inside temples near their homes because temples were a safe place, a neutral area, and a weapon-free zone.

“I’ve heard from the old folks that those who did not want to get involved in the battle stayed in temples for their safety,” Phinit says.

Phinit Prachumrak, aka Seu Noi, a 72-year-old former teacher

Safe zone in temples

Phinit says that during that time, local residents brought food to temples and cooked their meals there, similar to when they made food at the temple to make merit. But at that time they essentially had to live there.

“People brought food and shared it with others, as best they could. They could not go out to catch crabs, fish, or frogs anymore,” he says. “They only had pla ra in [clay] jars for making chili paste.”

Residents fled to temples during the battle because they were afraid of becoming collateral damage in the crackdown against the rebels, many of whom were executed. Back then, Prince Sapphasitthiprasong, the Bangkok-appointed governor of Ubon Ratchathani, used heavy-handed measures. Thus, people were too afraid to leave home and go out to work.

“I’ve heard that they killed all the men that they saw,” Phinit says. “Only women were spared because women were seen as unthreatening to them.”

A map of Ban Saphue at Wat Burapha, Trakan Phuet Phon district, Ubon Ratchathani province

Nikhom Promsrimai, a local resident of Ban Saphue

Story of Kaew Duangdee

Buddhist temples were not the only place people sought refuge. While Buddhist beliefs, such as that of the Bodhisattva Maitreya played an important role in the emergence of the Holy Man Rebellion, people also turned to the shrines of local spirits in times of suffering and mortal conflict.

That’s what happened in Ban Saphue in circumstances surrounding the battle. Nikhom recounts stories he heard from his grandparents about how the residents in his hometown sought shelter during the battle. Two notable tales are about a man named Kaew Duangdee, and another about a refuge at the shrine to a local spirit.

- PART I: The Holy Men Revolt: A Tale of Two Countries

- PART II: The Holy Men Rise and Fall Across Borders

- PART III: The Role of Champassak Royals as Mediators

Kaew Duangdee was a Ban Saphue resident. During the Battle of Non Pho. Kaew went into a bamboo forest to hide. Laughing, Nikhom says, Kaew could not get back out because he got caught in bamboo thorns. It was not until the battle was over that the villagers could cut away at the bamboo to release Kaew.

Nikhom also says that some people fled to “Don Pu Ta,” the local spirit that watched over the village. It was where residents worshiped for a good harvest and protection of the village from all harm.

“In the past,” Nikhom says, villagers “followed Don Jao Pu or Don Pu Ta. My grandparents said many people hid all over the place around here. When the fighting reached this area, people from the government hunted for the villagers [who had taken refuge at the shrine] but they couldn’t see them. It was believed that it was because the local spirit had protected them. That was what my grandparents told my parents.”

A mural depicting the Battle of Non Pho in 1902 at Wat Burapha of Ban Saphue, Ubon Ratchathani province

Life-and-death symbolism

During a battle, a symbol or an item of clothing could identify which side people were on. For the Battle of Non Pho, wearing a palm leaf hat meant siding with the Holy Men. Women who had to travel close to Non Pho wore a flower behind their ears to show that they were not with the rebel movement.

Prayun Khaisaeng, a descendant of a prominent local leader in Ban Saphue, says a palm leaf with ancient Khmer inscription on it was a symbol of a rebel. Anyone wearing it was in immediate danger. If they were seen by soldiers, they were regarded as one of the Holy Men.

“My parents told me that they (the government soldiers ) ] were searching Ban Saphue,” says Noei Sareebut, a local female mor lam performer at Ban Saphue. “Those who did not remove the palm leaf were decapitated. Those who took it off in time lived. Parents and old people in the village rolled husbands into mats and hid them on a ceiling joist.”

“Anyone wearing a palm leaf hat was killed,” says 72-year-old Prayun Khaisaeng, a former policeman. “There was a combatant wearing a palm leaf hat and someone told him to take it off. Otherwise, the soldiers would kill him.” Prayun motions toward the back of his house, pointing out where he had heard the execution site was. “My grandmother told me many people died here, at the back of my house. That was where they decapitated people.”

According to former teacher Phinit, those who delivered food to the soldiers had to wear a white flower behind their ears as a symbol that they were not a threat, showing that they were there just for delivering food and water, whether it was for the rebels or the government.

A mural depicting the Battle of Non Pho in 1902 at Wat Burapha of Ban Saphue, Ubon Ratchathani province

The legend of Kuan Wiangjan and his Ring of Black

While talking to a group of villagers about the Battle of Non Pho, Prayun tells a story about his great grandfather, kuan Wiangjan. He says the word “kuan” might refer to a position of kamnan, or a local chief, because Kuan Wiangjan was the chief of Ban Saphue at the time.

“Kuan Wiangjan was my grandmother’s father,” Prayun says. “My grandma told me that before the battle broke out at Non Pho, he set up troops…marched them across the field to station themselves at a big paddy field. The main troops were actually at Non Bo Lalai. [The rebels] had palm leaves tied around their heads. They battled at this village, at Non Pho.”

“I don’t know how many days [the battle was],” Prayun admits. “I didn’t ask my grandparents. When they told me, I was a child. I just laid there and listened.”

Prayun Khaisaeng, a 72-year-old former teacher

“Kuan Wiangjan was a key figure in the village who was in contact with the government,” he said. “When anything happened, he alerted the young people to hide inside their houses and not to come out.”

Beyond helping the residents take shelter during the battle by passing on information he received from the government, Kuan Wiangjan also took part in the crackdown against the Holy Men. According to Prayun, there were several pieces of inheritance that Kuan Wiangjan passed down in his family, including a mahout’s hook, while he himself had received a ring.

That ring has always remained mysterious to Prayun. “I used to have the ring of Kuan Wiangjan, the one he wore while executing people. It was a big black ring that looked like metal. I once scratched it and saw it was red-gold inside. Then, about six to seven days later, it was solid black again. It had naturally turned black again on its own.”

There is no clear evidence of what Kuan Wiangjan looked like. The only things remaining are the stories of him that have been passed down through the generations, including his personal belongings scattered among his descendants who have since moved elsewhere.